Space medicine

Article curated by Holly Godwin

Space travel has many associated risks; some of the causes we understand, some are yet to be explained. Astronauts are entering an alien environment, little of which has been explored and, as a result, researchers are still in the process of analysing the dangers involved.

Risks of radiation in space

We are exposed to far more radiation in space than we are on the Earth’s surface. This difference in electromagnetic environment means that some of the research into the effects of radiation on the human body carried out on Earth are not directly transferrable to the effects on the body in space. So while we do have an understanding of radiation as a phenomenon, there is a lot we don’t know about the effects it can have.

The difference in radiation levels is predominantly due to the Earth’s magnetic field, which acts as a shield against any approaching radiation, deflecting the high energy charged particles from the surface. Spacecraft orbiting the Earth are not protected by the field, and if anything can run into problems due to it – the way the magnetic field forms results in areas of trapped particles, known as the Van Allen radiation belts. A spacecraft that is set on course to travel through a radiation belt will experience a far greater dose of radiation.

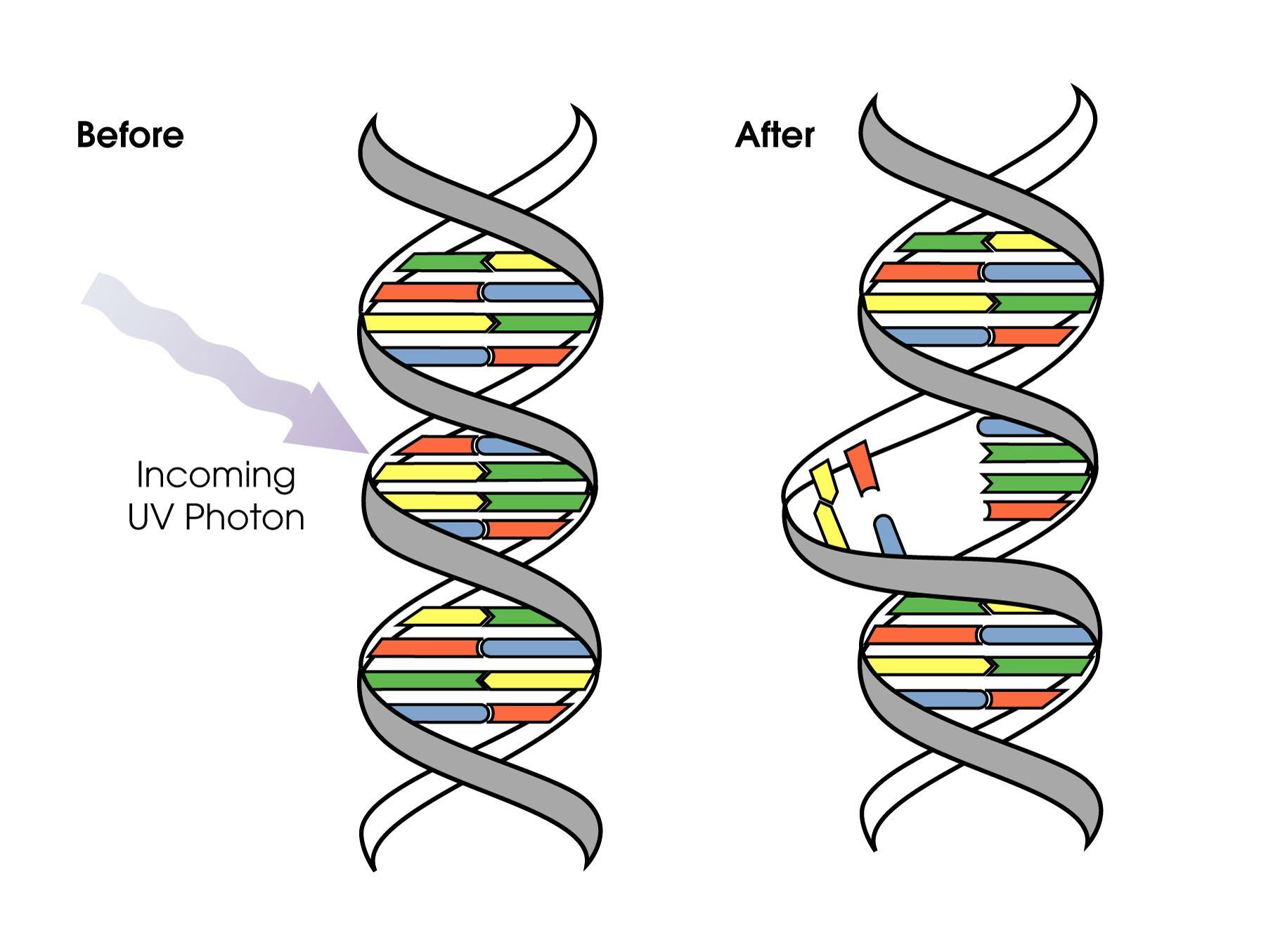

When highly ionising radiation passes through the body, the bonds in the DNA strands surrounding its path can be damaged. It is possible for DNA to repair damage done to one strand, however if both strands are affected successful repairs become unlikely. This leads to mutations and cell deaths, which translates into medical issues such as chromosome alterations and cancers.

Learn more about /mars.

2

2

Experiments in the International Space Station have shown that Deinococcus bacteria may be able to survive exposed in outer space for an estimated 8 years[1]. In the 3 year experiment, 96% of bacteria died; their DNA was fried and they became unable to grow or reproduce. However, some bacteria shielded by others lived, giving the theory of panspermia – that life on Earth may have originated from space travelling microorganisms – some footing.

Learn more about The smallest astronauts ever.

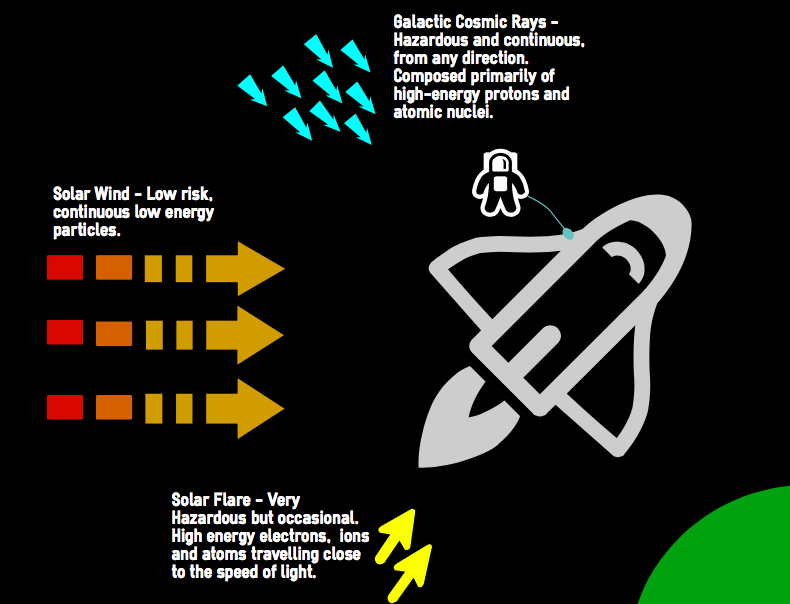

Sources of radiation – cosmic rays

We can separate the harmful radiation into two categories: radiation from within our solar system (predominantly solar radiation, which poses a threat when released in the form of a solar flare), and radiation from outside our solar system (such as >galactic cosmic rays (GCR)).

Given the Sun’s relative proximity to us compared to other stars, it is the main source of radiation within our planetary system. However, very high levels of cosmic rays have been recorded, which, after much speculation, are currently attributed to supernovae[2] – the cosmic rays are emitted like shrapnel from a bomb (the supernovae), and high energy particles are accelerated and flung out into space. However, this still doesn’t account for all the cosmic rays recorded, which leaves us asking – is this because there are more supernovae than we are aware of? Or is there another source of cosmic rays?

Cosmic ray acceleration

One consideration to take note of is that the cosmic rays could undergo acceleration, which could account for the higher energy rays detected. There are a number of theoretical explanations for this acceleration, including a mechanism known as First-Order Fermi acceleration. This involves a shock front accelerating particles to great speeds – in the case of a supernova, a shock wave follows an initial burst of expelled radiation, expelling most of the star’s mass. This process is still, however, inadequate at explaining the highest energy cosmic rays, which suggests there’s still something we don’t know. More research is necessary to understand cosmic rays, however studies on Earth are limited by factors such as the deflection cosmic rays experience from the Earth’s magnetic field and (for the cosmic rays that are detectable at the Earth’s surface) their interaction with the elements in the upper atmosphere.

How much is too much?

This is a comparably unexplored branch of science and there is a relative lack of data concerning the radiation experienced in space. For example, we don't know the maximum dose of galactic cosmic rays that the human body can be exposed to before a lasting and damaging effect occurs, and such a phenomenon would be hard to explore on the Earth’s surface. Consequentially, this is such an important area of research, as space exploration will be limited until we fully understand the ramifications of space radiation.

Evidence suggests radiation may be hormetic: that is, high doses inhibit normal processing, but low doses stimulate it. If so, this means it would actually be bad for us to completely shield us from radiation, and that there is an ideal, low exposure dose that would minimise toxicological consequences. It’s possible that we rely on low levels of background radiation to stimulate our immune systems and other biological functions.

More research is required to unravel how and why this happens, and whether effects differ between different sources of ionising radiation[3].

Learn more about /hormesis.

2

2

Living in microgravity – bone and muscle loss

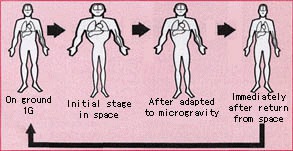

It's a common misconception that gravity is not experienced within a spacecraft, due to terms like ‘zero gravity’ (zero-g) and ‘weightlessness’. In reality, gravity can be found everywhere in space, at least in small amounts. This weaker gravity experienced in space is known as microgravity, where the forces are just a millionth of those experienced on Earth. These unique conditions can lead to health problems for astronauts, so must be fully investigated.

On Earth, sodium retention is associated with general fluid retention. However, a study investigating fluid retention of an individual on the MIR 92 and MIR 97 missions found that sodium was retained, but the fluid levels remained constant[4][5]. This increase in sodium is due to an activation in certain hormones in the microgravity environment, and we can't explain it yet. We do, however, now that it presents dangers for astronauts, as the increased sodium levels stimulate bone resorption (due to acidity) and result in a loss of bone mass over time.

The current limited data on the body’s homeostatic mechanisms means we just don’t know why this happens. However hopefully this wont be the case for much longer – The European Space agency has launched an investigation into sodium loading to verify whether sodium retention is a universal phenomenon and deduce the cause or causes behind it.

Astronauts, and people that are bed-ridden for extended periods, also experience serious muscle atrophy, in addition to bone loss. Astronauts spend much of their time attempting to compensate for this through an intensive exercise regime, but scientists on the ground are also trying to better understand it and find ways to prevent it from happening.

Curiously, bears somehow manage to hibernate for months on end without having problems with bone or muscle mass. If we can understand what is it about their physiology that enables them to do this, it could go a long way towards finding a solution in humans.

On the other hand, we don't have it as bad as birds: precisely because of our muscles. Birds, it turns out, can't survive in space because they can't drink. Whilst many birds can use peristalsis like humans – sequential contractions of muscles in the food pipe to swallow – many can't. Thsi could pose a potential problem if we think about what animals we could take with us to visit or populate other worlds.

– vision degredation

After some astronauts reported changes in the quality of their vision post-launch, studies were carried out in 2012 on 27 astronauts to examine the effects of microgravity on the eye[6]. MRIs performed before and after launch revealed multiple cases of bulging optic nerves and flattened eye balls. However, as all of the astronauts had been on previous missions, there was no control group for comparison.

It has been speculated that these effects could be attributed to the behaviour of fluids in microgravity. The reduced gravity could cause bodily fluids to shift from the lower extremities to the head – and this, in turn, could cause an increase in pressure within the skull (intracranial pressure), affecting the eyes.

While this does give some indication to why vision degradation occurs, it's not conclusive, and it does not explain why some astronauts suffer optical changes while don't. It's been suggested that maybe there are more factors that affect whether an individual is susceptible to intracranial pressure in microgravity, and ongoing investigations are exploring the role of nutrition. To fully understand this risk, far more research is necessary, and a greater understanding into the behaviour of liquids in microgravity will be fundamental.

– heart rhythm disturbances

Astronauts have presented with heart rhythm disturbances post-flight, which have generally been attributed to cardiovascular disease. But were these conditions pre existing, but undiagnosed, or developed out in space? We've already established that the heart undergoes physiological changes in microgravity, particularly when longer term exposure to microgravity is concerned. It is possible that these structural changes of the heart could alter its electrical conduction, but we are lacking in evidence to suggest that these alien conditions are to blame for recorded rhythmic abnormalities. More rigorous screening procedures prior to missions are being implemented, to rule out any chance of the disturbances being due to pre existing conditions, and further research will be carried out into the behaviour of the heart. Until this is complete, we just don’t know.

With hopes to colonise Mars and a drive to keep exploring further, we must first gain a better understanding of this hostile environment. Current research will hopefully provide a clearer insight into the risks associated with space travel, but undoubtedly more will arise... The leaps and bounds made in space exploration during the last century were immense. With all this new understanding, and the unknown stretched out in front of us, the next step seems within touching distance. However to think we’ve even scraped the surface would be ridiculous, and to dive in unprepared would be ill advised. Remember: in space, no one can hear you scream..

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Ed Trollope, Jon Cheyne, Johanna Blee, Rowena Fletcher-Wood, and Holly Godwin.

This article was first published on 2015-08-27 and was last updated on 2021-08-02.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Kawaguchi, Y., et al., (2020) DNA Damage and Survival Time Course of Deinococcal Cell Pellets During 3 Years of Exposure to Outer Space Frontiers in Microbiology 11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02050.

[2] Ackermann, M et al. Detection of the Characteristic Pion-Decay Signature in Supernova Remnants. Science Magazine (2013):807-811.

[3] Luckey, Thomas D. Radiation hormesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Dose-response 4.3 (2006): dose-response.

[4] Aubert, André E, Frank Beckers, and Bart Verheyden. Cardiovascular function and basics of physiology in microgravity. Acta Cardiol 60.2 (2005): 129-151.

[5] Heer, Martina. Sodium regulation in the human body. Current Sports Medicine Reports 7.4 (2008): S3-S6.

[6] National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Risk of Spaceflight-Induced Intracranial Hypertension and Vision Alterations. Human Research Program (2012).

Recent space medicine News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles