Pregnancy

Article curated by Rowena Fletcher-Wood

There are many unknowns when it comes to pregnancy, and many accepted phenomena are still unexplained, or simply attributed to "hormones" or "the placenta" (a complex and poorly understood organ!).

Morning Sickness

Animals also get it. In a study of 202 female rhesus monkeys, it was found they systematically rejected foods or certain foods both whilst they were ovulating and in early pregnancy, peaking around week 5[1].

There are three main theories for morning sickness:

1. Prophylaxis – the embryo protects itself by making the mother averse to potentially dangerous foods. In particular, women experience aversions to strong-tasting bitter things, which are potentially abortifacient, and, even more strongly, to animal products such as meat and eggs, which carry a high risk of parasites and pathogens. One cross-cultural study found 7 traditional societies that had no history of morning sickness, and noted that they were significantly less likely to include animal products in their diets[2]. Women who feel sick also have a higher probability of a healthy pregnancy.

2. By-product – sickness is a nasty side effect that serves no direct purpose, caused by mother and baby competing over essential resources or the hormones associated with viable pregnancies.[3].

3. Social indicator – letting others know a woman is pregnant to ward of sexual partners and increase social support (there seems to be nothing in the literature at all about this!).

During the critical first trimester, most women get sick and go off bitter things, including coffee. This has completely messed up medical research into the effects of caffeine, because it’s difficult to untangle high consumption from lack of sickness. Some research suggests excessive caffeine consumption magnifies other negative effects[4].

Learn more about Alcohol and Caffeine (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #9).

Advice on relieving morning sickness is also controversial. Many tricks don’t have an explanation behind them, such as ginger, used for centuries as a sickness remedy, and still unexplained – or sea bands, which apply acupressure, an eastern medical technique that currently remains unsupported by scientific evidence. Another controversial remedy is vitamin B6, which comes with both studies showing no effect[5], and studies showing effectiveness in treating morning sickness[6].

Learn more about Morning Sickness (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #1).

The Thalidomide Scandal

In 1953, thalidomide was prescribed for morning sickness, but then over 10,000 babies were born with deformities. The molecule, it turns out, is handed, which means it comes in right-handed and left-handed versions, and the left-handed version appears to be responsible for birth defects.But is the right-handed version safe? We don’t actually know. Initially, thalidomide was identified as harmful when birth defects were statistically observed in 20% of thalidomide babies (above the normal average of 1.5%). However, years later, higher than usual rates of dyslexia, autism, or epilepsy were also observed, and we’re not sure how thalidomide causes any of these.

2

2

There are more than 30 proposed mechanisms for how thalidomide caused these birth defects, and in fact, it looks like more than one could be true. Mechanisms include causing mutations in DNA and cartilage, interfering with neural networks, generating reactive oxygen species (which accelerate cell ageing in the body), and inhibiting some proteins[9]. It is also antiangiogenetic, which means it stops the development of new blood cells – exactly what happens when the placenta is forming between 6 and 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Learn more about The Placenta (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #4).

3

3Cravings and aversions

Along with sickness, many pregnant women experience cravings. The reason for this is often vaguely explained away by hormonal changes, but the specific reason is still unknown. Medical advice is to follow cravings, which may signal the need for certain nutrients.

At the extreme end, some women suffer from pica, a craving for non-food things like dirt. Many crave ice cubes – which is directly linked to iron deficiency[10]; however, research has shown that pica sufferers with low iron do not necessarily crave iron rich foods – scientists can’t explain why.

.jpg)

Learn more about /smell.

2

2

Embryo development

There are many things we still don't know about the very first hours of an embryo's development. In this time, does an embryo separate its back from front? Left from right? Or is this decided later?

We know some of the orders of development, but usually in more detail later in the cycle when the embryo is looking more like a baby. We still don't know what drives cells to specialise into organs and functions and how the initial shape and structure takes hold. This is of especial interest to those making moral decisions about when an embryo changes from a bunch of cells to an independent living thing.

Learn more about Embryo development.

Menstruating when pregnant

Morning sickness is a common symptom of pregnancy, but traditionally, a woman twigs she is pregnant when she misses a period, but this doesn’t happen to everyone. Some continue having “periods” for one, two, or more months. Whilst they are not truly menstruating, doctors can’t explain every bleed. Common explanations are implantation bleeding (when the embryo embeds into the uterus lining), subchorionic haematoma (where blood collects between the placenta and uterus lining), or miscarriage. Minor causes might be tears, inflammation, or infections. Around One in five women experience some kind of bleeding during pregnancy[11].

Unusual pregnancies

Masked symptoms, pseudomenstrual bleeding, and faulty tests play a part, and some suggest there are adaptive reasons that a pregnancy may not always be obvious.

Learn more about /unusual pregnancies.

2

2

We don’t know how long cryptic pregnancies last because the women who get them didn’t know about it at the time. However, some think they last longer or shorter than recognised pregnancies.

Learn more about Cryptic Pregnancies (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #20).

2

2Phantom pregnanciesSome weird pregnancies are not really pregnancies at all. For example, phantom pregnancies. Sometimes, like in many cryptic pregnancies, there is no medical evidence of pregnancy, but the woman still labours under the impression that she is pregnant. This is known as pseudocyesis, or delusion of pregnancy, or phantom pregnancy. Phantom pregnancies can also occur in males, and can last significantly longer than recognised pregnancies, some for many years. We don’t know why phantom pregnancies come about, but it correlates strongly with the post-menopause period and weakly with psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, other psychotic disorder, mood disorders and organic brain disorder [12][13][14][15].

3

3

Learn more about Superfetation (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #21).

3

3ParthenogenesisParthenogenesis, or asexual reproduction, has never been observed in humans, but does occur in animals, including sharks, snakes, lizards and insects. Considered a last-resort tactic for species survival, parthenogenesis occurs when two of the mother’s eggs combine to create the embyro. In 2001 at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha, a female bonnethead shark that had been kept in all-female captivity for three years gave birth to a female pup that was later DNA tested and found not to have any male shark contribution. It is not known to what extent parthenogenesis has impacted animal lineages.

3

3

Sleep

Some researchers have linked poor sleep to longer and more difficult labour and delivery, with women sleeping less than 6 hours a night 4.5 times more likely to undergo caesarean operation. Others found that shorter and easier deliveries were linked to labour nightmares, and hypothesised that this was because women were “practising” in their dreams!

Learn more about /foetal and maternal sleep.

4

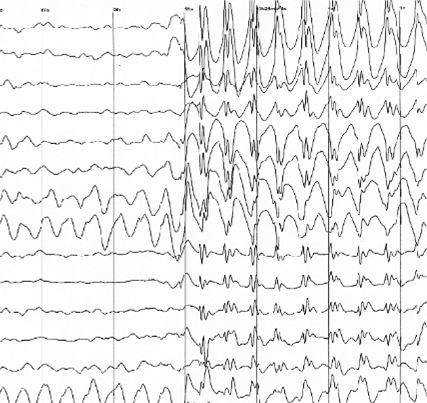

4We can’t measure the brain activity of a human foetus – not whilst they’re inside their mother. Researchers into brain activity instead perform EEG (electroencephogram) exams on premature babies and monitor eye movement to tell them about sleep cycles, although errors are common.

3

3Using these methods, REM (rapid eye movement) sleep sleep is detected from around 7 months, when the brain cycles in and out of restful and REM sleep every 20 to 40 minutes and the foetus sleeps 90% of the time. Very little is known about foetus sleep before this.

3

3Opinion is divided when it comes to whether foetuses sleep more at night or day. Until 3 months old, they don’t produce their own melatonin – so rely on mum. But does it work to make babies sleep? Many babies are soothed by their mother walking, and this persists after birth, with motion such as rocking sending them to sleep, whilst stillness makes them wake up.

3

3

Another area of research is the relatively un-navigated territory the relationship between foetal health and maternal sleep. Some studies think that the mother can influence her child’s health by sleeping well when she’s expecting, but the cause-effect relationship between impaired sleep and infant health is a difficult web to untangle!

Learn more about Foetal health and maternal sleep.

3

3Skin

Learn more about Bizarre symptoms (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #3).

Weight

In the US, health professionals obsessively monitor women’s weight whilst pregnant. However, the correct amount of recommended weight gain during pregnancy is debated scientifically[16], and the weighting process is often counter-productive because it makes women worry.

Weight gain goes towards growing the placenta (1.5 pounds), amniotic fluid (2 pounds), increased tissue masses (4 pounds), extra fluids (4 pounds), increased blood volume (4 pounds), and, of course, the baby (7.5 pounds). A further 7 pounds is stored nutrients, including fat, believed to be a vital resource during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Scientists don’t know exactly how this happens – only that it’s controlled by hormones.

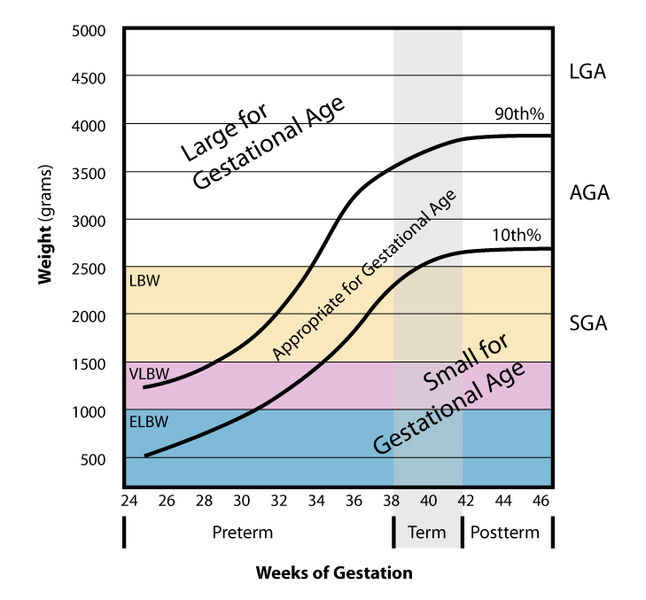

Because baby growth is affected by what you take in, weight affects baby size. Very large or very small babies are at risk of more complications, especially small for gestational age (SGA) babies. SGA babies carry a risk of cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive complications, whereas SGA (large for gestational age) babies cause birth problems – usually leading to caesarean[17]. Or, in other words, small is bad for baby, big is bad for mother.

Statistical analyses of competitive athletes (not climbers) has shown that women who are extremely fit are less likely to have overweight babies and equally likely to have underweight babies, with a slightly lower average weight. Since women who are very fit are less likely to be overweight, and overweight women tend to have heavier babies, this could just be a biased sample effect.

But weight gain during the pregnancy is not the only thing that affects baby weight. Even more important is when the baby is born – early, late, or close to their due date, any conditions the mother may get like gestational diabetes, and her starting weight.

Over- and underweight women can be at increased risks of pregnancy complications. However, overweight and obese women are still recommended to gain weight during pregnancy – just less. Being obese carries a chance of reduced fertility, higher incidents of miscarriage, stillbirth, birth defects, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, sleep apnea, blot clots, and a tricky delivery/recovery. It can also complicate spotting birth defects. Being underweight carries the risk of premature birth and SGA at birth – and so risk of cardiovascular, respiratory and digestive complications in the newborn.

Learn more about Weight (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #2).

Height

Why do shorter women have shorter pregnancies? Researchers looked at the records of nearly 3500 births and discovered a connection between height and pregnancy length. The team don't know the exact cause yet, but believe it must be in a set of unknown genes. It was added that a "woman's lifetime of nutrition and her environment" are likely factors too.

2

2

Microbes and genes

![Baby By Beth [CC BY 2.0], via Flickr](/img/sci/baby.jpg)

Learn more about Microbes and genes.

3

3Caesareans

Are caesareans risky? Maternity mortality rate for caesarean section is now only 3 times that of vaginal births[23], but this may be because a number of caesareans are only carried out in emergencies. Caesareans may also reduce the risk of complications in some cases: for women who have previously had a caesarean section, choosing an elective one for a subsequent baby over a vaginal birth reduces the risk of complications or consequential health problems (such as womb damage) from 1.8% to 0.8%[24]. Overall risk remains minute.

Regardless of whether elective or emergency, a review of 20 million births across 61 studies has shown that babies born by caesarean are a third more likely to develop autism and a sixth more likely to develop ADHD[25]. Possible explanations include:

- Confounding factors that contribute to the likelihood of a caesarean, like an older mother, defective placenta, or premature baby.

- Use of antibiotics during the operation.

But it seems unlikely it is linked to mode of delivery.

Studies have shown that parents recognise their own baby’s cries above those of others and are more responsive to their needs due to an amplifying effect of the hormone oxytocin[26] [27]. The effect, however, is not as strong if the baby is delivered by caesarean section[28]. We’re not sure why.

Interestingly, fathers are equally good at recognising their own baby’s cry as mothers, but, for some reason, they are less sensitive to oxytocin and giving them more doesn’t seem to increase their sensitivity to baby cries[29][30].

We can use oxytocin to initiate labour, but how does it happen naturally? Does the foetus initiate labour? If so, how? We don't actually know, but the foetus may be responsible – or one of many factors.Researchers have found two proteins in mice that eventually lead to the promotion of labour. These proteins, SRC-1 and 2 (steroid receptor coactivators) produce pulmonary surfactant components, which in turn begins the birth. Two of these components specifically, SP-A and PAF, are very important in the start of labour because a lack of them caused an up to two day delay in the mice. If that was in a woman, it could be up to a month late! Further, when injected into mice lacking these components, labour was initiated[31].

2

2Exercising whilst pregnant

Exercise is good for you – but how much exercise is good for you when you’re pregnant? Recommendations are ever-changing, and for some sports, such as climbing, there are no controlled studies for performing whilst pregnant.

However, one literature review found that women who exercised at high intensity had a range of reduced pregnancy symptoms, including:

- 1/3 the rate of gestational diabetes

- 2/3 the rate of preeclampsia

- 1/4 the rate of low back pain

- Lower chances of deep vein thrombosis

They also showed a better ability to tolerate heat stress, and shorter, easier labours, including:

- 1/3 the rate of epidurals

- 1/4 the rate of induced labour

- 1/4 as many caesarean sections

- Lower chances of umbilical cord tangling

It even lowers the risk of ‘baby blues’ and postpartum depression.

Because of these general benefits, it’s impossible to say whether certain exercises, such as prenatal yoga, are in any way beneficial. Studies are not only performed on women who are already fitter than average, but also tend to be performed by people already biased towards yoga, and involve only small groups of women (such as 25).

2

2

However, during pregnancy, the body changes and remodels itself; the hormone relaxin relaxes ligaments and loosens joints, making injuries like dislocations and pulled muscles more likely. Centre of gravity shifts, upsetting balance, and oxygen increases, with an extra 20% of blood flowing, which can make a pregnant woman’s blood pressure drop, leaving her more prone to dizziness. As such, pregnant women should avoid any exercise that might make them dizzy and so fall over (which could injure her or her baby), including lying on their back for prolonged periods. This is why so many yoga positions are contraindicated, such as inversions, along with the more obvious sports such as skydiving and horseriding. Other positions, like standing twists, can put also pressure on the abdominal cavity, which, in the worst case scenario, could lead to placental abruption. Similarly, other high impact sports like kickboxing, judo or squash are not recommended, where the bump could get hit. However, the risks of these exercises are minimally studied, and advice is simply not to do them.

How much exercise to actually do varies person to person.

Beginners should pick whole body sports that don't involve moving in any very new way and so minimise risks of injury, like walking, swimming and running, for 150 minutes or so a week. However, for fitter women, this would involve reducing exercise: experts recommend you carry on with what you’ve been doing (climbing, pilates, badminton…) and tell your instructor you're expecting in case anything needs to be adapted.

In the past, pregnant women used to get told not to let their heart rate go above 140 beats per minute, but this arbitrary number has been slacked off as it doesn't really tell us much about safe limits. Instead, look out for signs that you're unwell, including:

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Extreme thirst

- Swelling

- Chest pain

- Vaginal bleeding

- Contractions

Scientists are investigating how, but it seems getting too hot and staying too hot for prolonged periods has been linked to malformations and birth defects in unborn babies, especially during the first trimester. This has led some people to avoid exercising hard. However, you’d have to run very fast for at least a couple of hours to get your body temperature near the danger zone. Studies on competitive athletes who work out at above 90% their recommended maximum heart rate have so far shown no increase in birth defects. “Hot yoga”, “hot pilates” and saunas, however, are deemed hot enough to pose some risk.

Learn more about Exercise (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #8).

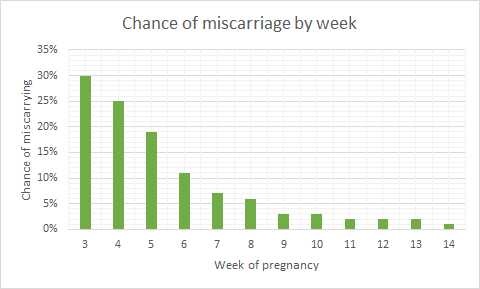

Miscarriage

Miscarriage is a common medical complication that leads to the loss of a pregnancy before 23 weeks, and affects 1 in 4 women during their reproductive lifetime. Most miscarriages make themselves evident with symptoms including abdominal pain, discharge, and vaginal bleeding. These symptoms can abate, or progress to the expulsion of the foetal tissue after days or even weeks. However, once it’s started, we don’t know any way to stop it: nature simply runs its course. Sometimes the uterus doesn’t empty out properly, and an operation has to be performed called dilatation of the cervix and curettage of the uterus (or D & C).

There are five main reasons for a miscarriage:

(i) genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, where a foetus inherits a faulty gene, or copying errors occur when cells are dividing early on[32].

(ii) lifestyle factors such as smoking, drinking, obesity, or malnutrition

(iii) health conditions like uncontrolled diabetes, thyroid disease, high blood pressure, food poisoning, infections (especially in the uterus), trauma, or hormonal disorders – or the use of non-compatible medications.

2

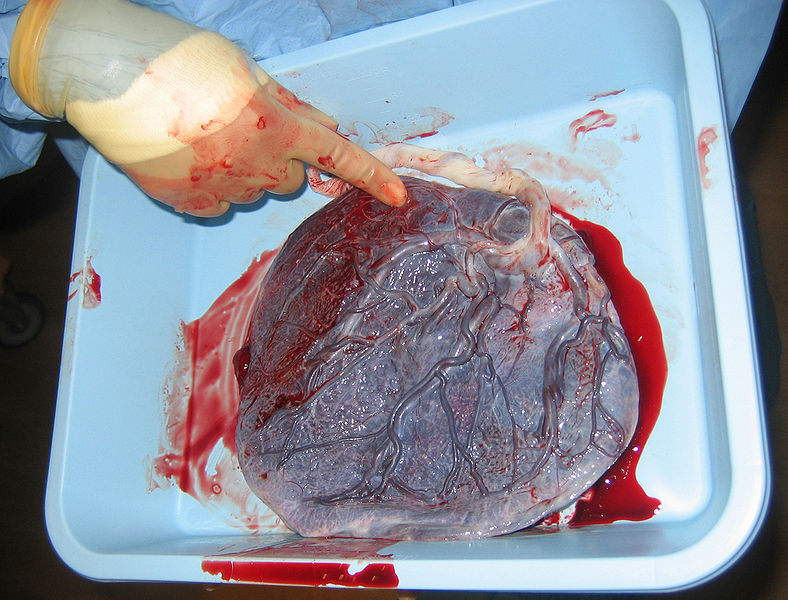

2(iv) mis-implantation – when an egg implants outside the uterus (usually on the walls of the fallopian tube). This is a medical emergency because the placenta develops a complex network of blood vessels between the mother’s tissues and the baby’s – meaning that when it peels away at birth, massive internal bleeds can happen if it’s not attached to the uterus, a muscle that contracts to stem the bleeding. Around 1 in 80-90 pregnancies are ectopic in the UK.

(v) placental problems: which can be affected by blood disorders, trauma, or multiple pregnancies, amongst many things. Amongst things that can go wrong, insufficiency (not passing the baby enough nutrients) and abruption (coming off the uterus wall too early) are linked to miscarriage.

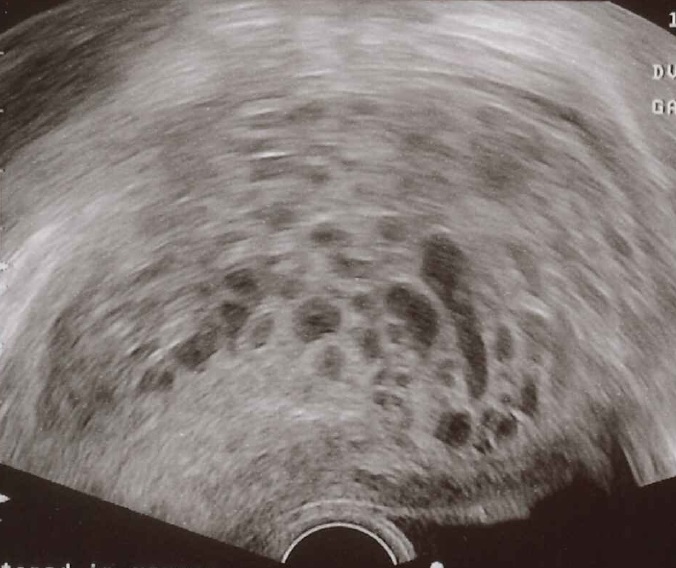

Molar pregnancies, for instance, are non-viable pregnancies where cells develop to look like a bundler of fish eggs, but don’t form a foetus. No one knows why they happen, but they have to be surgically removed – occasionally by full hysterectomy.

Learn more about Silent Miscarriage (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #11).

2

2When the amniotic sac that usually contains a foetus develops without the foetus in it, this is known as a blighted ovum or anembryonic pregnancy. The empty sac means that the fertilised egg never implanted, or didn’t develop properly, and instead got reabsorbed back into the uterus. Whilst this happens early on, if the placenta continues growing, it makes all the hormones associated with pregnancy anyway, masking the loss. Normal pregnancy symptoms progress, and the sac often has to be removed surgically. Scientists don’t know what causes a blighted ovum, but it could be linked to complications chromosome 9 and is more common if the parents are biologically related.

Read more about miscarriage and ongoing research on the topic here.

2

2The placenta

The placenta is a complex and poorly understood organ. A two-sided disc, one side develops from the mother’s tissues 7-12 days after conception and sticks to the womb, and the other forms 17-22 days after conception from the blastocyst that starts off the foetus, once it has connected up with the mother’s blood supply. Scientists are still studying how the placenta forms.

Mostly when something foreign enters a woman’s body, her immune system attacks it. Scientists are still trying to uncover why she doesn’t also kill off a foetus. Understanding the process could reduce miscarriage frequency (~10% of pregnancies).

At the end of its life cycle, the placenta starts to break up. For placenta-sharing twins, this can sufficiently limit their oxygen and nutrient supply that doctors will induce the mother early. We don’t know why it breaks up early, but it might help detach it from the womb wall so that it can be expelled in the “third stage of labour”.

Towards the end of pregnancy, the placenta passes antibodies from the mother to the baby that weren’t allowed to transfer earlier, conveying passive immunity to the baby for about 3 months. But only some kinds of antibodies can pass – ones acquired a while ago. Diseases caught and fought off whilst pregnant don’t transfer!

A new study has reported the vertical transmission of the coronavirus COVID-19 from mother to unborn baby during the second trimester of pregnancy[37]. We don't know how it overcome the placenta. Abnormalities were found in the foetus, and placental insufficiency diagnosed. It’s not clear whether the virus took advantage of the placental insufficiency, or caused it, but no other cause was identified.

For more about the placenta, see our blog post or article on the subject.

2

2Toxoplasmosis

One such disease is toxoplasmosis, contracted from toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan parasite that will infect a third of people over their lifetimes.

Women who’ve contracted it toxoplasmosis before becoming pregnant are immune, and will pass on that immunity. The danger is contracting it for the first time whilst pregnant and passing on congenital toxoplasmosis, which can cause miscarriage or stillbirth, or birth defects that may not develop until adulthood, including seizures, jaundice, liver enlargement, hearing or vision loss, low IQ, neurological disorders and mental disability.

Doctors still don’t understand how toxoplasmosis works, and can’t treat it, though new anti-malaria, anti-schizophrenia and nanoparticle-borne antibody drugs are being explored.

Learn more about /toxoplasmosis.

2

2

Healthy adults humans are usually asymptomatic (though some get flu-like symptoms) and are considered dead-end accidental hosts, because toxoplasma gondii can only reproduce in cats – and wants to get back in cats. Some people think that toxoplasmosis can even change your behaviour, driving you to like cats, hang out with cats and, if you’re a rat, end up eaten by cats so the parasite can get back in cats.

2

2

However, you can’t toxoplasmosis directly from cats: you have to handle cat poo (where the eggs are excreted) or soil. This is why some foods, such as “unwashed greens” are best avoided during pregnancy – they might be soil contaminated and the soil might contain toxoplasma gondii – washed greens are safe to eat.

Meat is the primary source of toxoplasmosis (30-63% of infections in Europe[38]), and is dangerous when undercooked (especially pork, lamb, and venison), cured (like salami), raw (such as oysters, clams, or mussels), or unpasteurised (dairy products).

Learn more about Toxoplasmosis (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #6).

Things to avoid and environmental exposures

There are lots of things pregnant women are advised to avoid, including mobile phones, fire retardants, non-stick coatings, and endocrine disrupting chemicals such as bisphenol A and phthalates, found in many plastics and personal care products.

Whilst eating fresh rather than processed foods, minimising painting and use of cosmetics (or fancy pregnancy oils, creams and other unnecessary personal care products) are sensible moves, the exposure levels to these things are so low that they’re pretty much negligible anyway. However, these things do create confounding factors that make assessing the impact of particular foods, drinks or chemicals difficult if not impossible to quantify.

Many women turn to herbal teas as an alternative to caffeinated beverages, but be careful to do your research if you choose this path: not all herbal teas are safe for pregnant women. Herbal remedies tend to be unregulated, and natural concentrations of components can vary wildly, making amounts on packets rough guidelines at best. One recommended, safe tea is peppermint tea (which can even ease nausea), whilst chamomile is not a good idea (it can trigger uterine contractions).

Nettle tea, meanwhile, is sometimes recommended, and sometimes recommended against.

Learn more about /hormesis.

Research in mice has shown that the reproductive potential of mice born to paracetamol-ingesting mothers is reduced. The males were less aggressive to other males and couldn't mate with the females, whilst the females were born with fewer eggs, becoming infertile earlier. We're not sure how the study translates to humans, however. At the moment, women are advised not to take ibuprofen, aspirin, and other painkillers, but paracetamol is considered okay. Is this wrong?

Vitamins and supplements

Supplementing is generally advised for all pregnant women – but should it be? Do we actually absorb many of the nutrients in tablets, and do they make any difference? Scientists have shown that taking high, regular doses of multivitamins is actually proven to increase your risk of heart disease or cancer[39]. We don’t know why (it could be because of the fibre). However, supplementing is advised to ensure you get enough of some nutrients, including vitamin B12 (cobalamin). This vital nutrient supports the functioning of the nervous system and blood formation and is only found in trace amounts outside meat and dairy products, except in fortified foods like cereals. Researchers are unsure whether vegan sources of B12 are adequate. It's also unclear whether or not pregnant women should eat much oily fish. Fish contains omega 3 fatty acids – vital nutrients essential for brain development, blood and heart regulation – but also mercury. Is the risk worth it, or should it be avoided? Mothers are being pulled in two different directions.Vitamin D may need to be supplemented for in winter: helping the body absorb calcium for building baby bones, it's found in fish, eggs, dairy, fortified breakfast cereals, beans, and green leafy vegetables, and is made by the body when exposed to sunlight.However, more care should be taken over vitamin A. Whilst essential for growth and development, and healthy eyesight and immune system, the liver stores it, and can accumulate dangerous levels, whereupon it starts to act as a toxin and cause birth defects in babies. Healthcare professionals can advise on the correct amount.Similarly, folic acid is needed in high quantities (10-20 times the normal requirements) in early pregnancy, but research suggests that getting too much folic acid later in pregnancy can mask vitamin B12 deficiency[40] and may increase the risk of autism[41]. Research continues.

2

2

Other diseases

Autoimmune disorders may be triggered by harmful bacteria, viruses, or certain drugs, which mess up the body’s ability to differentiate between normal, healthy tissue and harmful substances. It could also have a genetic factor.

If your red blood cells are coated in an antigen known as rhesus D, you are rhesus positive. If they’re not, you’re rhesus negative. Rhesus state is inherited from the mother or a father, so a rhesus negative mother could carry a rhesus positive foetus if the father is also rhesus positive. In the UK, 85% of people are rhesus positive.

A pregnant rhesus negativewoman can come into contact with rhesus positive blood either when the placenta peels away during childbirth, or earlier if maternal and foetal bloods mix, such as after a fall or during a prenatal test. This sensitises the mother to rhesus positive blood, amplifying her immune response to it next time – usually during a second pregnancy. If the mother’s immune system attacks a foetus, this can lead to jaundice, heart failure, or enlarged organs. The mother herself won’t feel symptoms though – only the foetus suffers.

Rhesus disease is normally treated blood transfusion or early delivery.

Anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease that pregnant women can get, where anti-phospholipid antibodies are produced by the immune system. These attack the pre-embryo or trophoblast (outer cells from the blastocyst that give nutrients to the embryo and eventually become placenta), preventing it from staying implanted, and alter blood flow to the uterus. No one is sure why this comes about.

Mental health

Pregnancy is a time of great vulnerability, so it may come as no surprise that mental health conditions are higher for women on average around pregnancy (including during and just after) than any other time. Women's mental health, however, remains misunderstood and chronically underdiagnosed, as do the instances of pregnancy- or birth-centred mental health conditions in men. Many women’s conditions such as complicated births are treated physically, but the mental aspect is under-researched and rarely addressed, including birth trauma, postnatal depression, and grief following a miscarriage.

Learn more about /perinatal mental health.

3

3

Symptoms include flashbacks, high anxiety, low mood and avoidant behaviours.

3

3Postnatal depression is thought to occur in ~1 in 10 mothers, making it a common form of mental illness. The onset and peak of the illness may be weeks or even months after the birth of a baby, and the condition lasts for weeks, months, or longer.

3

3It also occurs in men, where it is chronically underdiagnosed.

3

3

3

3

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children looked at 3,176 father and child pairs, where they found not only did 1 in 20 fathers developed postnatal depression, but this correlated with a small but significant increased risk of daughters (but not sons!) developing depression at age 18[43]. Scientists are unsure why the effect is only seen in girls.

3

3There is no conclusive medication used to treat postnatal depression, but many options including drug alternatives such as hormone therapies, acupuncture, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), or transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Evidence is inconclusive[44].

3

3Postpartum bipolar disorder, the least well-known postpartum mental health disorder, is characterised by mood episodes of mania, hypomania or depression that interfere with everyday life and performing ordinary tasks. We don’t know the cause.

3

3Postnatal (puerperal) psychosis is an uncommon but severe condition, which can include low mood – or manic mood – delusions, hallucinations, and out-of-character behaviour. No one’s sure what causes it, but trauma or a history of other mental illnesses are risk indicators.

3

3

![Lateral View of the Brain By BruceBlaus [CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](/img/sci/Blausen_0101_Brain_LateralView_512.png)

Learn more about Baby Brain (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #14).

2

2NestingIs nesting, cleaning, organising, decorating and stockpiling in preparation for a baby biologically or socially driven?

Animals nest from birds to fish, rodents, cats, dogs, pigs, and 80% of pregnant women. Pregnant dogs will steal blankets, cats will climb into haylofts, rabbits pluck out their own fur to line the burrow, sows leave the herd to travel up to 6.5km[50], and broody birds will insist on constant nest sitting. Hormones have been linked to it, but up to 90% of men in a relationship with a pregnant woman show some kind of symptom (weight gain, morning sickness, mood swings, fatigue, disturbed sleep, labour pains(!)…) – leading to the alternative suggestion that it may be social.

Learn more about Nesting (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #5).

2

2

The endometrium

Scientists know very little about the endometrium – the uterus lining. The wall of the uterus changes during the menstrual cycle and accepts the implantation of a fertilised egg during pregnancy[51]. As such, it is known that the endometrium responds to female sex hormones, but not which or how. It also produces its own chemicals.

IVF and infertility

Now, scientists think that IVF failure may be just due to timing. IVF works by suppressing the natural menstrual cycle, stimulating and gathering eggs, and then reintroducing fertilised eggs. If they are introduced too early or too late, however, the womb may not be ready to receive them, and they will be lost. For most women, this timing is guessed, but a pilot study that individualises treatment by studying women’s uterine cycles has shown a 33% success rate.

Immunological treatment, however, remains controversial. It’s hard to entangle immunological factors in success stories from other factors such as individualised support, changes in diet, and medical attention.

Some clinicians think high levels of natural killer cells from the uterus, might be associated with miscarriage. However, they may have a different role there to in the blood, remodelling blood vessels through the placenta; in fact, some research suggests low numbers of natural killer cells in the uterus may obstruct pregnancy and that they perform a benign role, preventing other immune cells from attacking the foetus[52][53]. There’s also no agreed way to get natural killer cell counts. Blood levels and uterine levels are not necessarily linked, and levels in the uterus vary with the menstrual cycle.

Statistical analyses of 21 antibodies have found no differences in implantation rates, pregnancy rates, or pregnancy outcomes for higher or lower concentrations. Some treatments have been outright refuted, such as leukocyte immunisation therapy, which may be dangerous[54][55].

Alloimmune disease might also affect fertility. Alloimmune disease happens when the female body launches an immunological attack on male tissues – basically killing off his sperm.

Semen and pre-eclampsia

However, in contrast to alloimmune responses against a partner’s sperm, exposure to sperm may sometimes prevent pre-eclampsia, a life-threatening pregnancy complication that sometimes arises in the second half of pregnancy[56]. This may be due to immune modulating factors in the seminal fluid.

Learn more about Reproductive Immunology (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #7).

Biological sex

Identifying the biological sex of an unborn baby can be difficult, even with ultrasound: sometimes the baby just doesn’t cooperate, and accuracy only rises to 100% after 14 weeks gestation, with a success rate starting at 75% during the 12-week scan [57]. For some, knowing the sex of their baby early is especially important if they carry a serious genetic disease that affects one sex. For these women, invasive techniques may be used to collect foetal DNA, which can increase risk of miscarriage, so increasing ultrasound accuracy could save lives. Possible develops include cross-section imaging (allowing us to see “through” legs that are in the way).

To find out more about determining the sex of a baby, read our dedicated article on the subject.

Learn more about Determining the Sex of a Baby (Things We Don’t Know about Pregnancy Series #12).

Types of twins

Scientists are very interested in twins because it helps us identify the differences between genetic and environmental factors that influence health and behaviour. However, how twins form and the various types out there remains mysterious. For example, no one has ever seen cell fission – the explanation we rely upon to explain monozygotic (identical) twins.Other types of twins exist too. For instance, semi-identical or sesquizygotic twins: “in-between twins” that share 50% to 100% of their DNA in common: halfway between monozygotic (identical) and dizygotic (fraternal) twins. They are rare, we don't know how they come about, and there are several theories.

Learn more about /twins.

2

2Other strange types of twins include conjoined twins. These may arise from fission or fusion[58], but we don't know which. Do they come from incomplete egg splitting, or the twins growing together? If the latter, are they linked to additional limbs (which could be vestiges of absorbed twins), or even fetus in fetu, or one twin entirely inside another?

2

2Although as many as eleven internal foetuses have been identified, some scientists say these are not actually fetuses in fetu, but in fact a teratoma: a type of tumour that forms into whole organs or tissues such as hair[59].

2

2Partcularly common in twins is chimerism, a strange phenomenon where cells with the DNA of one person are found in the body of another. In particular, remnants of DNA of the mother have been found integrated in the brain of the child and vice versa[60][61][62]. Exchange of cells occurs across the placenta, twins exchange cells in the womb, and older siblings can even pass cells to younger ones via the mother. Male cells found in the brains of some women are notably fewer amongst women with Alzheimer's, suggesting they contribute to brain health.

2

2

What causes SIDS, and why mention it in pregnancy?

Sudden Unexplained Infant Deaths (SUIDs) of infants under a year old occur unpredictably and don’t have an obvious cause. Of around 200 such deaths in the UK every year, around 80% are classified as SIDS – Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (also know as cot death). These are the deaths that can’t later be explained by suffocation, infections, or genetic disorders, even after autopsy.

But what does this have to do with pregnancy?

Maternal health during pregnancy is a key indicator for SIDS risk. Some risk factors are a bit connected to pregnancy and a bit not, for example, minor illnesses (such as anaemia[63]); these can be out of your control, but chances may be reduced by staying healthy during pregnancy (in the case of anaemia, eating tons of iron-rich food) and getting all the requisite vaccinations.

Scientists think SIDS may be due to a combination of developmental challenges and environmental stressors, but there's still a lot we don't know.Check out our article on SIDS for more information.

Learn more about /sids.

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from McDowellG, Ginny Smith, Cait Percy, Johanna Blee, Kat Day, Rowena Fletcher-Wood, and Joshua Fleming.

This article was first published on 2019-10-19 and was last updated on 2021-03-29.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Czaja, John A. Food rejection by female rhesus monkeys during the menstrual cycle and early pregnancy.Physiology & behavior 14.5 (1975): 579-587.

[2] Flaxman, Samuel M., and Paul W. Sherman. Morning sickness: a mechanism for protecting mother and embryo. The Quarterly review of biology 75.2 (2000): 113-148.

[3] Flaxman, Samuel M., and Paul W. Sherman. Morning sickness: adaptive cause or nonadaptive consequence of embryo viability? The American Naturalist 172.1 (2008): 54-62.

[4] Hakim, Rosemarie B., Ronald H. Gray, and Howard Zacur. Alcohol and caffeine consumption and decreased fertility. Fertility and sterility 70.4 (1998): 632-637.

[5] Schuster, K., et al. Morning sickness and vitamin B6 status of pregnant women. Human nutrition. Clinical nutrition 39.1 (1985): 75-79.

[6] Chittumma, Porndee, Kasem Kaewkiattikun, and Bussaba Wiriyasiriwach. Comparison of the effectiveness of ginger and vitamin B6 for treatment of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Journal-medical association of Thailand 90.1 (2007): 15.

[7] Crystal, Susan R., and Ilene L. Bernstein. Infant salt preference and mother's morning sickness. Appetite 30.3 (1998): 297-307.

[8] Crystal, Susan R., and Ilene L. Bernstein. Morning sickness: impact on offspring salt preference. Appetite 25.3 (1995): 231-240.

[9] Vargesson, N., 2015. Thalidomide‐induced teratogenesis: History and mechanisms. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews, 105(2), pp.140-156.

[10] Borgna-Pignatti, Caterina, and Sara Zanella. Pica as a manifestation of iron deficiency. Expert review of hematology 9.11 (2016): 1075-1080.

[11] Şükür, Yavuz Emre, et al. The effects of subchorionic hematoma on pregnancy outcome in patients with threatened abortion.Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association 15.4 (2014): 239.

[12] Yadav, Tarun, Yatan Pal Singh Balhara, and Dinesh Kumar Kataria. Pseudocyesis versus delusion of pregnancy: differential diagnoses to be kept in mind. Indian journal of psychological medicine 34.1 (2012): 82. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.96167.

[13] Adityanjee, A. M. Delusion of pregnancy in males: a case report and literature review. Psychopathology 28.6 (1995): 307-311. doi: 10.1159/000284942.

[14] Chatterjee, Seshadri Sekhar, et al. Delusion of pregnancy and other pregnancy-mimicking conditions: Dissecting through differential diagnosis. Medical Journal of Dr. DY Patil University 7.3 (2014): 369. doi: 10.4103/0975-2870.128986.

[15] Manjunatha, Narayana, and Sahoo Saddichha. Delusion of pregnancy associated with antipsychotic induced metabolic syndrome. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 10.4-2 (2009): 669-670. doi: 10.1080/15622970802505800.

[16] Abrams, Barbara, Sarah L. Altman, and Kate E. Pickett. Pregnancy weight gain: still controversial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 71.5 (2000): 1233S-1241S.

[17] Emily Ostler, Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom is Wrong - and What You Really Need to Know (2013) Penguin Press.

[18] Fraser, Abigail, et al. Association of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring obesity and metabolic and vascular traits in childhood. Circulation 121.23 (2010): 2557.

[19] Reynolds, R. M., et al. Maternal BMI, parity, and pregnancy weight gain: influences on offspring adiposity in young adulthood. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 95.12 (2010): 5365-5369.

[20] King V, Dakin RS, Liu L, et al. Maternal obesity has little effect on the immediate offspring but impacts on the next generation. Endocrinology. 2013.

[21] Dominguez-Bello, M. G. et al. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11971–11975 (2010).

[22] Nature 572, 423-424 doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02348-3.

[23] Deneux-Tharaux, Catherine, et al. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. <Obstetrics & Gynecology 108.3 (2006): 541-548.

[24] Fitzpatrick, Kathryn E., et al. Planned mode of delivery after previous cesarean section and short-term maternal and perinatal outcomes: A population-based record linkage cohort study in Scotland. PLoS medicine 16.9 (2019).

[25] Zhang, Tianyang, et al. Association of cesarean delivery with risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA network open 2.8 (2019): e1910236-e1910236.

[26] Formby, David. Maternal recognition of infant's cry. Developmental medicine & child neurology 9.3 (1967): 293-298.

[27] Marlin, Bianca J., et al. Oxytocin enables maternal behaviour by balancing cortical inhibition. Nature 520.7548 (2015): 499.

[28] Swain, James E., et al. Maternal brain response to own baby‐cry is affected by cesarean section delivery. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 49.10 (2008): 1042-1052.

[29] Gustafsson, Erik, et al. Fathers are just as good as mothers at recognizing the cries of their baby. Nature Communications 4 (2013): 1698.

[30] De Pisapia, Nicola, et al. Gender differences in directional brain responses to infant hunger cries. Neuroreport 24.3 (2013): 142.

[31] Gao, L., Rabbitt, E. H., Condon, J. C., Renthal, N. E., Johnston, J. M., & Mitsche, M. A. (2015). Molecular mechanisms within fetal lungs initiate labor. Science Daily.

[32] Van den Berg, Merel MJ, et al. Genetics of early miscarriage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 1822.12 (2012): 1951-1959.

[33] Perez-Muñoz, Maria Elisa; Arrieta, Marie-Claire; Ramer-Tait, Amanda E.; Walter, Jens (2017). A critical assessment of the sterile womb and in utero colonization hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome. 5 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4. ISSN 2049-2618. PMC 5410102. PMID 28454555.

[34] Mor, Gil; Kwon, Ja-Young (2015). Trophoblast-microbiome interaction: a new paradigm on immune regulation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (4): S131–S137. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.039. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 26428492.

[35] Prince, Amanda L.; Antony, Kathleen M.; Chu, Derrick M.; Aagaard, Kjersti M. (2014). The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more questions than answers. Journal of ReproductiveImmunology. 104–105: 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006. ISSN 0165-0378. PMC 4157949. PMID 24793619.

[36] Hornef, M; Penders, J (2017). Does a prenatal bacterial microbiota exist?. Mucosal Immunology. 10 (3): 598–601. doi:10.1038/mi.2016.141. PMID 28120852.

[37] Sukhikh G, Petrova U, Prikhodko A, et al. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in second trimester associated with severe neonatal pathology. Viruses. 2021;13(3). doi:10.3390/v13030447.

[38] Cook AJ, Gilbert RE, Buffolano W, Zufferey J, Petersen E, Jenum PA, Foulon W, Semprini AE, Dunn DT. Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis. BMJ. 2000 Jul 15; 321(7254):142-7.

[39] Martínez, María Elena, et al. Dietary supplements and cancer prevention: balancing potential benefits against proven harms. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 104.10 (2012): 732-739.

[40] Morris, M.S., Jacques, P.F., Rosenberg, I.H., et al. (2007). Folate and vitamin B12 status in relation to anemia, macrocytosis and cognitive impairment in older Americans in the age of folic acid fortification. Am J Clin Nutr; 85(1):193–200.

[41] Beard, C. Mary, Laurel A. Panser, and Slavica K. Katusic. Is excess folic acid supplementation a risk factor for autism?. Medical hypotheses 77.1 (2011): 15-17.

[42] Liu, Can, et al. Prenatal parental depression and preterm birth: a national cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 123.12 (2016): 1973-1982. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13891.

[43] Gutierrez-Galve, Leticia, et al. Association of maternal and paternal depression in the postnatal period with offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA psychiatry 76.3 (2019): 290-296.

[44] Cole J, Bright K, Gagnon L, McGirr A (August 2019). A systematic review of the safety and effectiveness of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of peripartum depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 115: 142–150. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.05.015.

[45] Mascaro, Jennifer S., et al. Child gender influences paternal behavior, language, and brain function. Behavioral neuroscience 131.3 (2017): 262.

[46] Barha, Cindy K., and Liisa AM Galea. The maternal 'baby brain' revisited. Nature neuroscience 20.2 (2017): 134.

[47] Kinsley, Craig H., et al. Motherhood and the hormones of pregnancy modify concentrations of hippocampal neuronal dendritic spines. Hormones and behavior 49.2 (2006): 131-142.

[48] Gatewood, Jessica D., et al. Motherhood mitigates aging-related decrements in learning and memory and positively affects brain aging in the rat. Brain research bulletin 66.2 (2005): 91-98.

[49] Tomizawa, Kazuhito, et al. Oxytocin improves long-lasting spatial memory during motherhood through MAP kinase cascade. Nature neuroscience 6.4 (2003): 384.

[50] Wischner, D. Kemper, N. Krieter, J. (2009). Nest-building behvaiour in sows and consequences for pig husbandry. Livestock Science. 124 (1–3): 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2009.01.015.

[51] Diedrich, K., et al. The role of the endometrium and embryo in human implantation. Human reproduction update 13.4 (2007): 365-377.

[52] Moffett, Ashley, Lesley Regan, and Peter Braude. Natural killer cells, miscarriage, and infertility. BMJ 329.7477 (2004): 1283-1285.

[53] Vento-Tormo, Roser, et al. Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal–fetal interface in humans. Nature 563.7731 (2018): 347.

[54] Ober, C., Karrison, T., Odem, R.R., Barnes, R.B., Branch, D.W., Stephenson, M.D., Baron, B., Walker, M.A., Scott, J.R., and Schreiber, J.R. Mononuclear-cell immunisation in prevention of recurrent miscarriages (a randomised trial).

[55] Lancet. 1999; 354: 365–369; Hill, Joseph A., and Richard T. Scott. Immunologic tests and IVF: Please, enough already. Fertility and sterility 74.3 (2000): 439-442.

[56] Kenny, Louise C., and Douglas B. Kell. Immunological tolerance, pregnancy, and preeclampsia: the roles of semen microbes and the father. Frontiers in medicine 4 (2018): 239.

[57] Kearin M, Pollard K, Garbett I. Accuracy of sonographic fetal gender determination: predictions made by sonographers during routine obstetric ultrasound scans. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2014;17(3):125–130. doi:10.1002/j.2205-0140.2014.tb00028.x

[58] Joyce, J. Cyril. "Dextrocardia, Situs Inversus, and Twinning." British medical journal 2.4945 (1955): 950.

[59] Higgins, Kimberly R., and Brian D. Coley. Fetus in fetu and fetaform teratoma in 2 neonates: an embryologic spectrum?. Journal of ultrasound in medicine 25.2 (2006): 259-263.

[60] Opstelten, R., Slot, M. C., Lardy, N. M., Lankester, A. C., Mulder, A., Claas, F. H., ... & Amsen, D. (2019). Determining the extent of maternal-foetal chimerism in cord blood. Scientific reports, 9(1), 1-10.

[61] Koopmans, M., Hovinga, I. C. K., Baelde, H. J., Harvey, M. S., de Heer, E., Bruijn, J. A., & Bajema, I. M. (2008). Chimerism occurs in thyroid, lung, skin and lymph nodes of women with sons. Journal of reproductive immunology, 78(1), 68-75.

[62] Kelly, S. E. (2012). The maternal–foetal interface and gestational chimerism: the emerging importance of chimeric bodies. Science as Culture, 21(2), 233-257.

[63] Giulian GG, Gilbert EF, Moss RL (April 1987). Elevated fetal hemoglobin levels in sudden infant death syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine. 316 (18): 1122–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM198704303161804.

Blog posts about pregnancy

Recent pregnancy News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles