Planetary systems

Article curated by Grace Mason-Jarrett

Since the discovery that our solar system is not unique, astronomers have searched the skies for more evidence of planetary systems out there. NASA’s Kepler telescope has spotted thousands of potential exoplanets, all of which orbit a star. But some bizarre planets contradict our models, and seem to defy the rules we discerned by studying how the 8 solar planets behave. So we're starting again. By observing other systems, we hope to refine the laws governing planetary motion, and even to find evidence that life can exist on other planets.

Making the planets

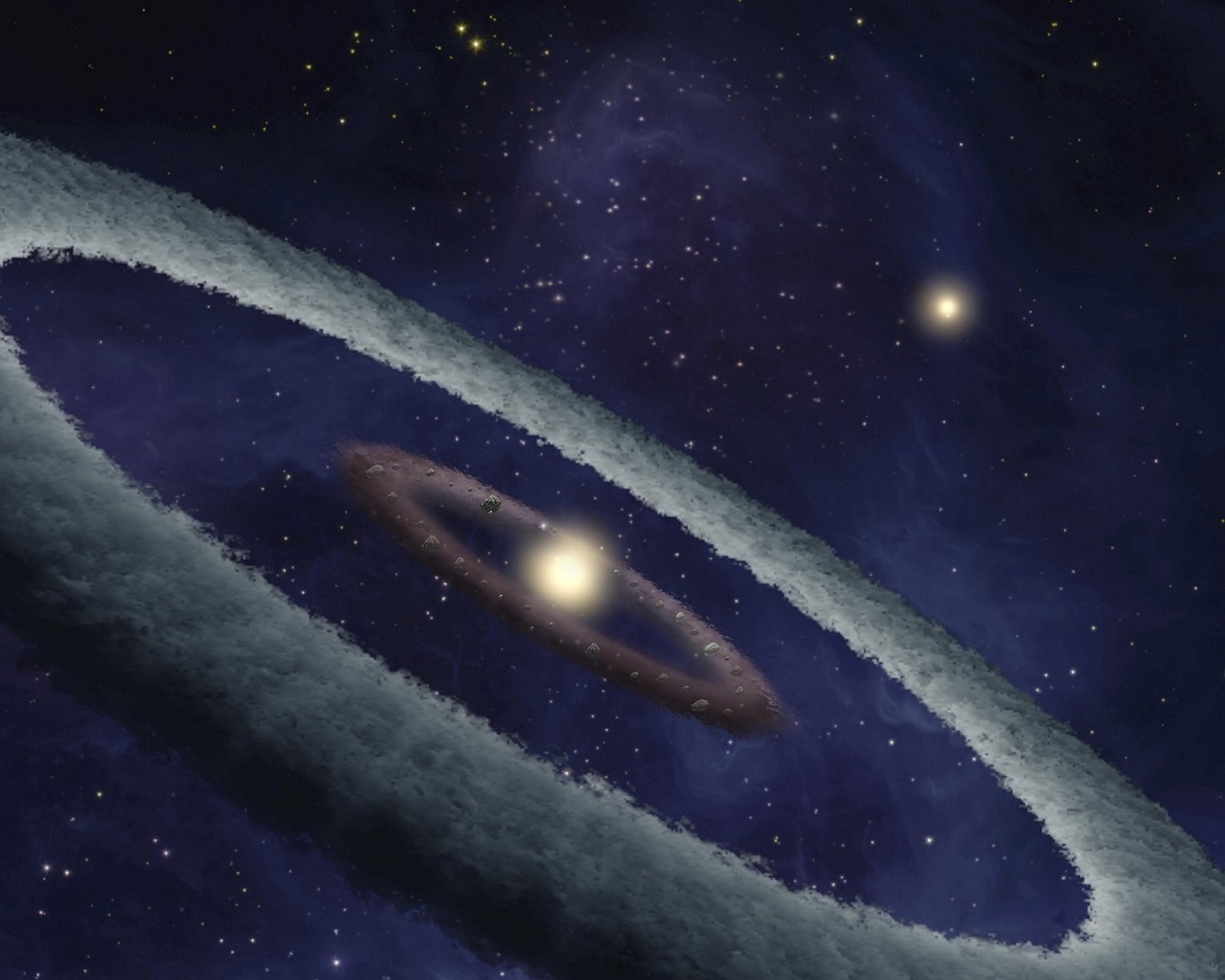

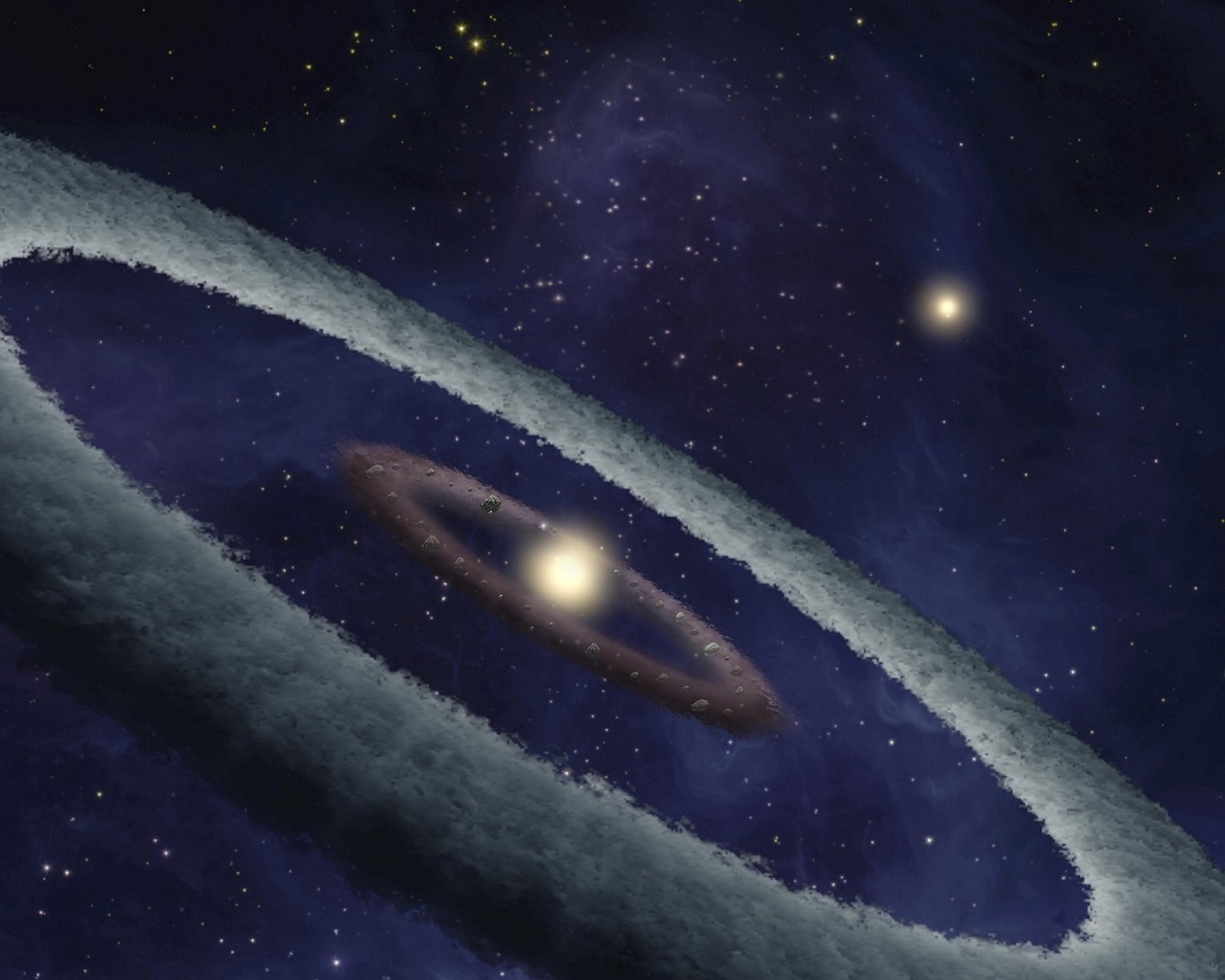

So how exactly do we get planets? The most popular theory at the moment suggests that most planetary material comes from the dusty remnants left over from when a star is born. However, new data indicates that the disc of dust surrounding a star shortly after its creation can completely disappear within a few years[1]. Perhaps this is a result of planet formation, all the dust being quickly gathered together forming young proto-planets. At the moment, we don’t have enough evidence to come to a definitive conclusion. It’s very difficult to observe exoplanetary systems forming, since this could take millions of years. Our best chance for finding answers is to observe as many planetary systems as possible at all different stages of their lifetime, which could take years and years of data collection.

Exoplanets

Learn more about Exoplanets.

Not only do planets themselves vary in composition and structure, but the systems in which these planets sit appear to differ too. We associate gas giants with being further away from the sun, and yet Kepler has spotted several ‘hot Jupiter’ systems in which gas giants reside in orbits close to their host star. This shakes the foundations of our gas giant formation theories, which explain the planets’ existence by saying that they can hold onto so much gas precisely because they're so far from the sun. There are also systems where great discs of gas and dust extend for thousands of kilometres around the central star, known as ‘dusty disc’ systems. There could be any number of different systems out there which we haven’t even seen yet.

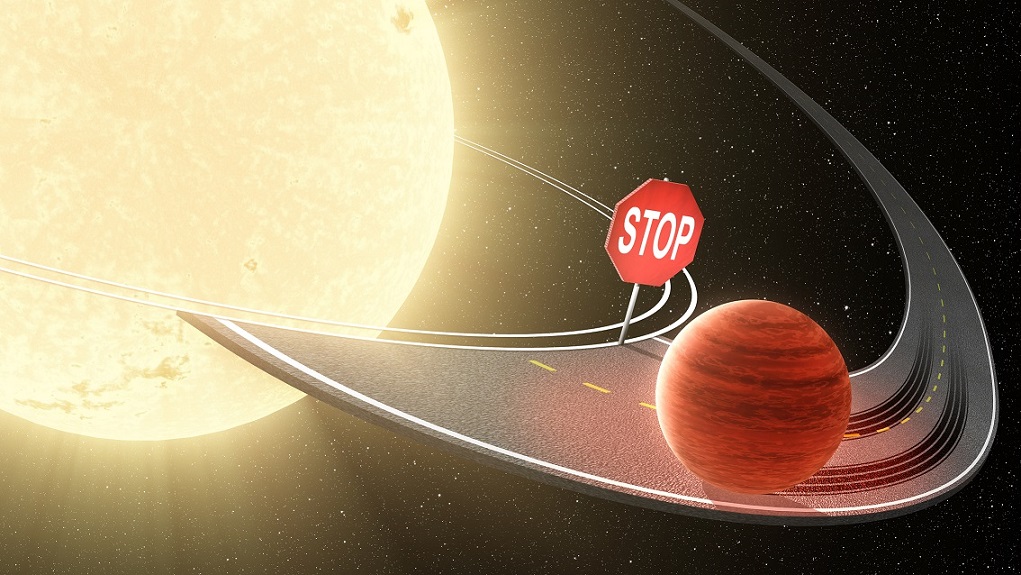

Why do planets orbit at the distance they do? One idea is that large, Jupiter-like planets are actually spiralling toward the central star, having formed at the distance allowed in our models; however, no planets have been found closer than a certain distance. So, is something causing them to stop? Are we somehow unable to see closer planets? Or have we just not found them yet? And if they do migrate towards the star, what drives them? A number of theories have attempted to answer these questions, but scientists are still struggling to find a theory that answers all of them – or, indeed, evidence[2]!

Finding exoplanets

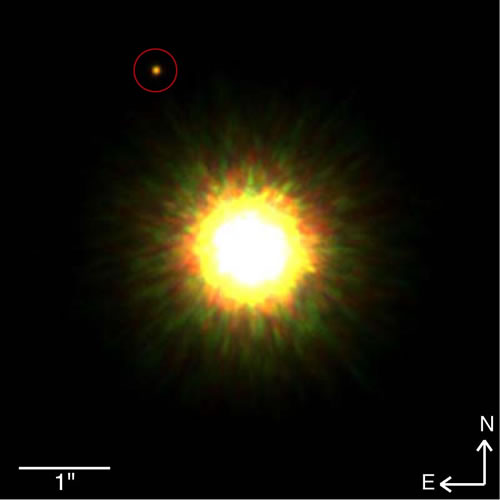

Unlike the direct observation of stars, the detection of planetary bodies requires astronomers to use a number of indirect methods to infer their existence. Due to the immense distances involved, the distance between any planet and their host star when viewed from Earth is tiny, and the brightness of the star itself effectively blinds instruments and obscures any planets in their orbit, which are much less bright by comparison. Therefore, astronomers have devised a number of ingenious methods to tease out planet data from their observations, but they require a great deal of skill, a generous helping of statistical analysis and a pinch of luck.

Learn more about Detection and Discovery of Exoplanets.

We have yet to image exoplanets directly... and it may be decades before the technology lets us. This makes finding out about how they orbit, what they're made of and how they evolved tricky, and scientists have to use techniques such as spectroscopy to make guesses about these exoplanets.

Learn more about direct imaging of exoplanets.

2

2This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Andrew Rushby, and Jon Cheyne.

This article was first published on 2015-08-27 and was last updated on 2021-05-18.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Melis, C., Zuckerman, B., Rhee, J. H., Song, I., Murphy, S. J., & Bessell, M. S. (2012). Rapid disappearance of a warm, dusty circumstellar disk. Nature,487(7405), 74-76.

[2] Alexander, R. D., & Pascucci, I. (2012). Deserts and pile-ups in the distribution of exoplanets due to photoevaporative disc clearing. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 422(1), L82-L86.

Recent planetary systems News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles