Pain

Article curated by Ginny Smith

Most of the time, animals try to avoid pain – from the simplest organism to the most complex brain on the planet. And so it's vital for our survival, teaching us that we're doing something that damages our body.

Pain is triggered when we damage our bodies – whether this is physical damage such as a cut or bump, chemical irritants such as acid, or extreme heat or cold. This damage triggers our nerves to send signals via the spinal cord to the brain, which creates the feeling of pain. But this process is a complex one, and there are many things about pain we still don't know. Perhaps the hardest of these to answer is what the experience of pain actually is. This question, being more philosophical than scientific, is one we may never be able to answer.

Learn more about Pain.

2

2The experience of pain

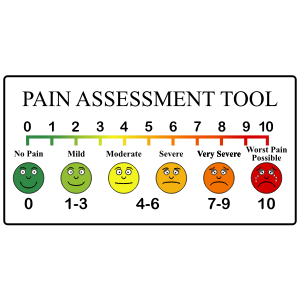

If you give two people the same injury, they may not experience it the same way, and we don't know why. Pain thresholds vary between people and between cultures. Gender, fitness and even hair colour can influence your tolerance, with redheads feeling pain more acutely thanks to a genetic variation linked to pain receptors. Depression and anxiety can also make a person more sensitive to pain. And surroundings even make a difference: for example, playing a video game can distract you from pain, and swearing profusely can operate as a relieving emotional outlet, having something sweet in your mouth or even holding the hand of someone you love[1][2]. How exactly these effects are mediated, however, isn't known. There is also surprising evidence that one side of your body may experience pain differently to the other side. It seems your dominant hand even interprets pain more quickly than your non-dominant hand.

People experience more or less pain almost by choice – because of attentional bias. The painful stimulus isn't entirely responsible for pain experience, but can be influenced by previous experiences and your feelings towards it. People who are afraid of pain exhibit a selective attentional bias towards it. That is, they focus more attentively on the painful situations in their life and therefore may 'feel it more'.

Those who show an attentional bias towards pain tend to engage in pain catastrophising – ruminating, magnifying it, and feeling helpless because of it. This is a well-known predictor of pain in those suffering chronic pain. In a study focused on pain back pain, it appeared that women were more likely to catastrophise their pain as a coping mechanism. The reason why is not understood.

Some people, however, are born with very rare genetic conditions giving complete insensitivity to pain. Often, they end up spending a lot of time in hospital for injuries they simply didn't know they were getting. They must actively learn and constantly be thinking about what things are "bad" to touch, such as knives or boiling water, because they will never feel the warning signs of a light prick or rising warmth. These people have no trouble experiencing the touch and feel of their surroundings, showing that pain isn't just an excess of touch. Instead, there are nerves which specialise only in detecting and transmitting harmful stimuli. These nerves are called nociceptors, and are probably the best understood aspect of pain[3].

The nociceptor pain receptors deliver their signal to a region of the spinal cord called the dorsal horn, where the arrangement of neurons is chaotic at best. The complexity here is so great that even categorising the different cell types[4] and functions is proving challenging, and this is before the nociceptive signal even reaches the brain.

Sex and gender

Sex hormones also contribute to pain experience. After the menopause, when a woman’s circulating female sex hormones drop, we see a much smaller difference in sex differences in pain. It's not clear why this is.

Amongst many other contributing factors, our sex and gender may have a profound impact on pain and our pain experience. Gender impacts our pain experience, and may play a significant role in how pain is differentially assessed and treated between men and women. This phenomenon has been deemed the ‘gender pain gap’.

Chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus, affect more women than men globally. In fact, 80-90% of people diagnosed with fibromyalgia are women, and more women than men live with a chronic pain conditions.

Fibromyalgia is a medical conditions characterised by pain throughout the body. The cause of fibromyalgia is unknown, although some people are thought to be more genetically susceptible than others. To date, research has linked fibromyalgia to abnormal levels of specific brain chemicals and unusual pain messaging systems in the central nervous system (brain, spinal cord and nerves). However, a root cause can not be definitively distinguished. The disease can be triggered by traumatic events such as a death, breakdown of a relationship, operation, birth, injury or infection. No current treatments for the disease exist, and symptoms are managed through a variety of interventions.

Some women experience pain on one side of their abdomen around 14 days after the start of their period. This pain is known as ovulation pain or mittelschmerz and can be sharp, dull, sudden, or prolonged for minutes or days, varying woman to woman. Doctors theorise that this happens during ovulation, but don’t know why or what part of the process the women are detecting. They also can’t explain why some women experience it and others don’t.

Vulvodynia is chronic vaginal pain without an identifiable cause and which may or may not be initiated by touching the area, having sex or inserting a tampon. ~9% percent of women will experience it in their lifetimes. It can also come and go. Scientists don’t have a clue why this is or where it comes from, but suspect it’s related to the extra nerve fibers in the outer part of the vagina and vulva. The pain is treated with medications such as lidocaine, which is used for fibromyalgia.

The literature is yet to catch up with the importance of accounting for sex and gender in pain research. One study found that 56% of all pain research articles referenced sex, and only 16% referenced gender[5]. Of those referring to gender, more than 75% were actually talking about sex, by definition. Nearly one third used sex and gender interchangeably.

Chronic pain

Chronic pain is thought to be mediated by the central nervous system, so treatments like aspirin that target the site of the pain are often not useful. Some people find opioid painkillers help, while for others they have no effect or even worsen symptoms. Chronic pain is either "nociceptive" (caused by inflamed or damaged tissue activating specialised pain sensors called nociceptors), or "neuropathic" (caused by damage to or malfunction of the nervous system). Why the pain persists long after any obvious injury should have healed is unknown.

One idea is that consistent activation of the pain system sensitises it, meaning low level stimulation that wouldn't've previously activated pain receptors starts to do so. In some cases, genetics predispose people to having low thresholds for pain signalling, causing chronic pain issues to arise. Alternatively, the differences may arise in the areas of the brain which process pain signals. Until we know more about how any why these conditions arise it is unlikely we will find treatments for them.

Refereed pain occurs when the sensation is felt somewhere other than the site of the damage. Its mechanism is unknown, although there are several hypotheses.

One type of referred pain is visceral pain which comes from the internal organs but is felt in places very remote from the location of the affected organ. It can often be a very useful tool to diagnose diseases of internal organs, for example is the pain in the arm felt during a heart attack.

Theories to explain this are mostly based on a lack of dedicated sensory pathways in the brain for internal organs. This means sensory neurons connect with sensory pathways that carry information from the skin and muscles, giving various places where they could become crossed over, and causing mixup. Other mechanisms have been proposed.

Pain can be felt even when there is no injury, and this just doesn't seem to make evolutionary sense. In chronic pain sufferers, a physical injury could leave a lasting pain, even after the tissue has healed. Why the pain of some injuries leaves with the wound and others linger for months, years or a lifetime is not clear, and the risk factors are not fully understood. Chronic pain sufferers are often passed back and forth between physical and psychiatric doctors because neither can identify the root cause, and so only offer symptom management.

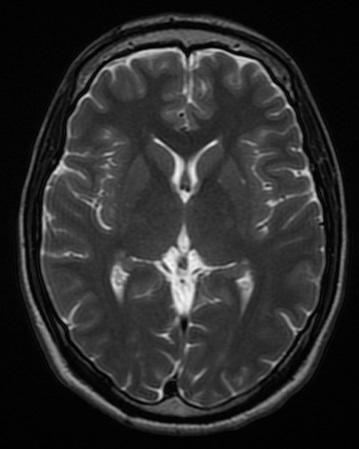

One of the most significant recent observations was made in 2004 when it was found that chronic back pain sufferers also had significant reduction in grey matter volume throughout the brain[7] compared with non-sufferers. This atrophy was most significant in parts of the brain known for relaying pain-related signals and processing the emotional and cognitive elements of the pain experience. The researchers noted that those suffering from back pain for longer periods of time showed more brain atrophy. They are now looking into why this might be the case.

Current treatment for chronic pain focuses around a combination of painkillers and various pain management therapies. Unfortunately many chronic pain sufferers develop tolerances to the most accessible painkillers, and the stronger ones like morphine are plagued with side effects and are therefore heavily regulated. What's missing is an in-between drug; one which can combat the abnormal pain while leaving the healthy pain pathways intact.

It can take years or even decades to develop brand new drugs from scratch. For this reason, there is also research into treating chronic pain with pharmaceuticals already on the market (and so known to be safe), but used for other conditions. These include anticonvulsants (primarily used to treat epilepsy) and antidepressants. The relationship between chronic pain and depression is complicated. Suffering with one makes you far more likely to suffer the other but antidepressants appear to work whether or not the pain sufferer also has depression – how exactly it does this is not known[8].

Placebo effect

One of the most mysterious effects known to science is the placebo effect. People experience all sorts of effects when given completely inactive 'treatments', known as placebos. Pain is particularly receptive to placebo treatments, but we don't know how they work, though they may trigger the body to release natural painkillers. Researchers are examining the brain function of those receiving the placebo vs ‘real’ treatments in a bid to understand how this process works.

There are factors that are known to change the efficacy of placebo treatment. 'Branded' placebos are more effective than 'unbranded' ones, and the size, shape and colour of the pill can also have an effect. Placebo injections are even more effective than pills, and surgery is more effective that injections. Fascinatingly, the effects can be seen even when patients are told that they are being given a placebo, suggesting there is something more complex going on than just the power of positive thinking.

2

2

Because of this, many believe that processes such as meditation and mindfulness could be effective pain relief. Whilst there are lots of anecdotal “proofs” that they work, these tend to come from people who are already convinced that mindfulness, meditation and, often, yoga, work. However, a recent study on meditation using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was able to show using whole brain analyses that meditating made you less sensitive to heat-induced pain via greater deactivation of the posterior cingulate cortex[9]. The study only involved 76 volunteers, who were first time meditators, so more work has yet to be done. –

Cramps

One interesting type of pain that science can't explain is cramping – the pain experienced when your leg suddenly seizes up. No one knows what causes cramping, and it's difficult to study because of the unprovocable nature of the problem – though some have tried. Occasionally it can be triggered by other conditions, and you’re more likely to get it if you’re older and heavier, but one thing’s for sure – cramping is not associated with too much or too little salt. The original salt theory was developed following the observation that stokers of fires got cramp more often – presumably because they were sweating out their salts. However, hot environments do not always lead to cramp, and measurements of salt levels of individuals experiencing cramp have not shown any significant differences from control groups.

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Emily Coyte, Ginny Smith, Johanna Blee, and Rowena Fletcher-Wood.

This article was first published on 2016-06-16 and was last updated on 2020-05-18.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Stephens, Richard, John Atkins, and Andrew Kingston. Swearing as a response to pain. Neuroreport 20.12 (2009): 1056-1060.

[2] Byrne, E. Swearing is Good for You. London. Profile Books; Main edition (2017).

[3] Welch, JM, SA Simon, and PH Reinhart. The activation mechanism of rat vanilloid receptor 1 by capsaicin involves the pore domain and differs from the activation by either acid or heat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97.25 (2000): 13889-13894. doi:10.1073/pnas.230146497.

[4] Todd, Andrew J. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11.12 (2010): 823-836. doi: 10.1038/nrn2947.

[5] Boerner, Katelynn E., et al. Conceptual complexity of gender and its relevance to pain. Pain 159.11 (2018): 2137-2141.

[6] Chahine, Lama, and Ghassan Kanazi. "Phantom Limb Syndrome-A Review." Middle East Journal of Anesthesiology 19.2 (2007): 345.

[7] Apkarian, A Vania et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. The Journal of Neuroscience 24.46 (2004): 10410-10415. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004.

[8] Sansone, Randy A, and Lori A Sansone. Pain, pain, go away: antidepressants and pain management. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 5.12 (2008): 16. PMCID: PMC2729622.

[9] Zeidan, Fadel, et al. Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. Journal of Neuroscience 31.14 (2011): 5540-5548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5791-10.2011.

Blog posts about pain

Recent pain News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles