Memory

Article curated by Ginny Smith

Our memories make us who we are, and yet we still don't understand how memories are stored in the brain, or what happens when problems develop.

Inside the mind

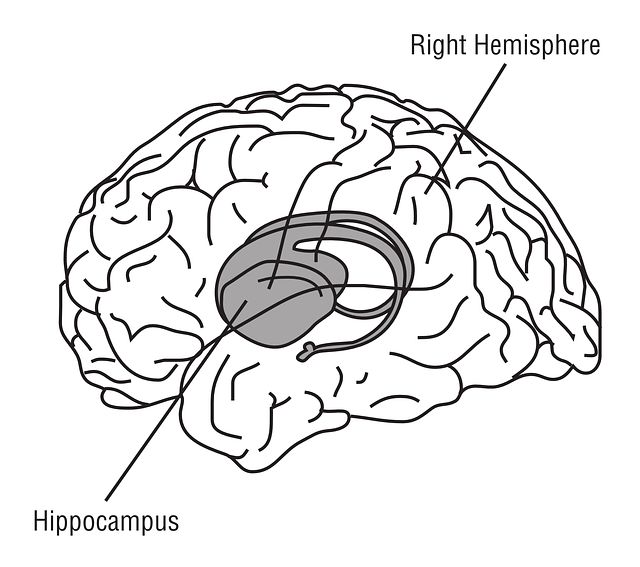

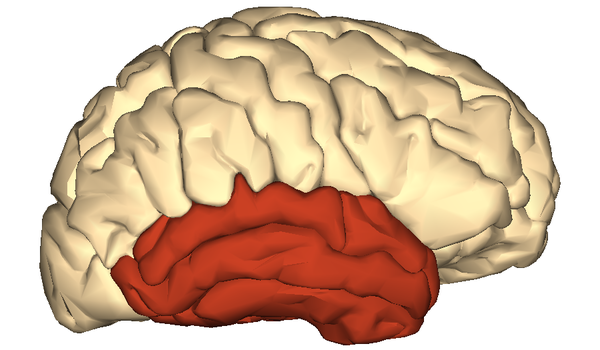

When holding an item in short term memory, the frontal lobe is highly active. Depending on whether the memory is visual or auditory, it will also activate regions of the brain responsible for that kind of processing. The hippocampus is vital for converting short term memories into long term memories, which are then stored somewhere in the cortex (the surface layer of the brain), depending on the type of memory.

Memories for events in your life, known as episodic memories, are thought to exist in a scattered network of neurons that allow recall of different sensations. Functional MRI experiments have shown that recalling sensation and undergoing them look the same in the brain. Other kinds of memory have their basis elsewhere: spatial memory, for example, is stored in the hippocampus, emotional memory involves the amygdala, and procedural memories memories, like driving, are stored in the cerebellum, the basal ganglia, and the motor cortex. Learning more about how and where the brain stores memories may help to improve the life of those with memory loss in future[1].

Learn more about Memory in the brain.

2

2Familiar faces

Humans are great at recognising faces. We used to think a specific region of the brain was responsible for face processing, but now scientists think that whole networks are involved. One famous study in this area claimed to discover a ‘Jennifer Aniston Neuron’ using single cell recordings: a neuron that responded specifically to pictures of the movie star, suggesting information about the identity of a face may be stored in a single cell. But we don't have enough cells to assign one to each of the people we've met. If you look at possible combinations of cells, however, the number is more than large enough. It was later discovered that the so called ‘Jennifer Aniston cell’ responded to information relating to her, as well as images of her.

Most studies have been done using faces that are unknown to the person looking at them, but processing unfamiliar faces is very inefficient, and we actually spend most of our lives surrounded by people we do know: and very little is known about how we process familiar faces. In one study, participants were asked to sort images into piles, one for each person who was represented. The images were taken from different angles and under different lighting conditions. Interestingly, when the images were of people known to them, participants could successfully work out that there were only two different people represented. When the people were unfamiliar, though, participants thought there were an average of 13 different people in the photos.

Forgetting

Cues also matter. Without a stimulus that was present at the time of encoding, sometimes we just can't recall a memory. Other memories can be interferred with, such as when new information is combined and confused with an older memory. How does this happen? It seems every time you recall a memory you relay it in your brain, so interference is something you can create, by always pairing a memory with a disparate thought when you recall it, until they are entwined.

Interestingly, we can also direct forgetting – consciously choosing to discard information. Brain imaging studies have shown this takes effort – we are actually disrupting the encoding or consolidation process, but how we do this isn't clear[2].

We are often told that in your mid-20s, your brain reaches its peak and then memory declines… but it’s not quite this simple. Episodic memory and your ability to ignore distractions seems to decline more with age than semantic memories or procedural memories memories – this is why you might forget where you left your keys, or what you went upstairs for. But different testing and control methods give different results – some think decline starts in your 20s, others not until your 60s! Some skills, such as vocabulary and general knowledge, often improve over time. Brain scanning studies have found all kinds of differences with age, including fewer brain cells, a thinner cortex, and smaller hippocampus[3].

2

2

Sweet dreams

One theory is that memories are formed during the day in rapid stores, but these are easily destroyed by new information coming in. Sleep allows slower but more permanent memories to form. However, recent studies have suggested that more is going on. It is now thought that active processes allow the gist of information to be extracted and combined with previously stored knowledge, although exactly how isn't known.

4

4Unusual memories

One theory is that the cues to the word you are searching for have caused your brain to recall a similar word, which then blocks the word you want. Alternatively, it may be that the activation level of the word is strong enough for you to detect that it is there, but not strong enough to access it. Another theory suggests that it's because we store memories in different ways, such as through motion, sound, colour or touch. Storing memories in varied ways allows us to pack more information in, but sometimes makes it harder to unravel.

Learn more about Tip of the tongue syndrome.

2

2Another common yet unexplained experience is déjà vu. Déjà vu means already seen and refers to the feeling that an event or location has been experienced in the past when it hasn't. The causes of déjà vu are poorly understood, and it's is difficult to study as there is no way of predicting it. However, several theories have attempted to explain this phenomenon. Some link déjà vu to processes involving memory: for example, suggesting it occurs when the brain undergoes processes similar to those experienced previously, leading to the feeling of familiarity. Others believe that the effect may be due to a momentary dysfunction of the nervous system. Unfortunately, until we find a way of inducing a déjà vu so scientists can observe it, it is likely to remain a mystery to us.

Learn more about Deja vu.

There exists a field called epigenetics. The Frenchman Lamarck is often laughed at these days for his evolutionary theory and giraffe example that animals required desirable characteristics through wanting them enough, and therefore imprinting that quality on their offspring, such as the giraffe stretching it’s neck to get food. But Lamarck may have been onto something, and that something is epigenetics: this field studies how things that happen to you in your life can imprint onto your DNA. Remarkable studies have shown that what happens to you in your life can be passed on, and can even skip a generation: going directly to your grandchildren, such as one study of cardiovascular health in adults whose grandparents went through famine. The study showed that the grandchildren had a higher risk for heart disease, because their bodies stored and retained fat more. However, recent findings go further. We might even be born with memories from our ancestors imprinted on our DNA, especially traumatic events. This could explain basic survival instincts, phobias and savants.

2

2

The theory of priming claims that non-conscious memories can affect your behaviour and actions, and these can be manipulated by your environment. For example, in one classic study, people walked more slowly after reading works related to elderly people. But others have failed to replicate this study using lasers to measure speed rather than error-prone humans with stopwatches. To check this, they repeated the study with human timers, who knew the hypothesis – in this version of the study, those students primed with elderly thoughts were found to walk slower. This was a huge blow to the initial study – could it be that unconscious bias from the experimenters was the reason for the initial findings? Elsewhere, hundreds of other studies which claim to have found similar priming effects, e.g. that priming with stereotypes can change behaviour to be more like that stereotype.

Scientists generally agree that long-term memories are encoded in synapses, according to differences in their signalling strength. But a competing nonsynaptic, epigenetic model of memory storage has been demonstrated in marine snails, which suggests instead memories are stored in the nuclei of neurons. When researchers taught snails to enhance their defence reflex from 1 to 50 seconds using mild electric shocks, then extracted their RNA and injected it into untrained snails. The injected snails were tested, and withdrew for 40 seconds.

2

2Memory disorders

After a stressful situation, some people are left with persistent flashbacks, hyper-vigilance, anxiety and depression; a condition known as post traumatic stress disorder or PTSD. Sufferers have an over-active adrenaline response, causing excessive fight or flight experiences, leading to long term changes in the brain.

We don’t know why some people who suffer a traumatic event develop PTSD while many others don’t. There seems to be a genetic component, but this only explains some variability. Having a smaller than average hippocampus has also been linked with vulnerability to developing PTSD. We know that the hippocampus is involved in storing memories in context, so if this area is under active, this could explain why the flashbacks experienced in PTSD are like re-living the event, rather than remembering it. Normally, the emotions associated with a memory fade with time through a process known as extinction. We think this is somehow disrupted in PTSD sufferers.

2

2In the future, we hope to be able to determine those at most risk of developing PTSD and take preventative measures. However, while there are a few medications which may improve symptoms available now, most PTSD treatments are psychological. One possible future treatment is propranolol, which is commonly used to treat high blood pressure. When a memory is recalled, it enters a labile state, where it can be changed. The idea is that by administering propranolol during recall, the fear-related heart rate increase is reduced, and the memory is stored again without the fear component. Most of the studies in this area have been done in mice, and there is limited evidence of whether it would work in humans.

2

2

Probably the most popular memory disorder portrayed in the media is transient global amnesia; characterised by sudden, complete memory loss. However, the real condition is rather different to media portrayals, and much rarer. Patients do lose recent memories (sometimes just a few hours, sometimes a year or more), and become unable to store new ones, so may keep asking the same questions. However, they retain memories reflecting who they are, are able to recognise people they know well, and the condition is usually temporary (~2-8 hours).

The cause of transient global amnesia is unknown, but for this diagnosis, it has to have no obvious physical cause like brain damage or seizure. It's more common in older people and those with history of migraine, and can be triggered by stress, strenuous physical activity, head trauma or sudden temperature changes. It could be some form of epileptic event, a problem with blood circulation in the brain, or a type of migraine.

As we age, many of us experience memory losses, but the one that many fear most is Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, but we don't understand why some people develop it and others don't. It is thought that a protein called beta-amyloid is involved in Alzheimer's. This protein often builds up in the brains of Alzheimer's patients, forming large plaques which are thought to block the normal functioning of the brain, and promote inflammation. However treatments to break down these plaques have had mixed results.

One theory suggests that it isn't the plaques themselves that are harmful to the brain, but a smaller, soluble version of the protein that does the damage. This fits with research that shows that the disease isn’t always linked with plaques, and breaking down the plaques in those who do have them can make their symptoms worse. Another protein, called tau, is also implicated[5]. Normally, it forms straight fibres which help transport nutrients and other necessary molecules around the brain. In Alzheimer's, however, it forms tangles, disrupting this process, and possibly causing cell death. The brains of Alzheimer’s patients are actually seen to shrink as the disease progresses; neurons and synapses are lost, particularly in areas responsible for memory, which may cause the problems. What causes this shrinkage, however, isn't known.

There is a strong genetic component to Alzheimer’s – early onset Alzheimer’s (before age 65) is associated with specific genetic mutations; however, the more common, later onset form is more complicated. While there are genes that have been linked to the illness, lifestyle and environmental factors such as diet are also important.

Galantamine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, is used to treat Alzheimer's and other memory conditions. Although its efficacy is not strong, it is one of the most effective treatments we currently have. Because we don’t understand Alzheimer’s well enough, we don’t know how to design better treatments. Galantamine can be chemically synthesised, but because it is chiral, syntheses can’t produce very much from reactants. This makes it expensive, and it's easier to extract naturally from certain species of snowdrops and daffodils. In Powys, huge fields of Alzheimer’s daffodils have been planted as a future source of galantamine. However, it’s also important that we’re careful with daffodils, as they contain the toxic alkaloid lycorine, from the same category of drugs as atropine in belladonna, which, taken in high enough doses, can cause dizziness, abdominal pain, nausea, convulsions, and death.

Learn more about Causes of Alzheimer's Disease.

2

2Improving memory

Physical exercuse, however, is one of the best things you can do for your brain – not that we know why. However, it seems it does several things, including reducing inflammation and improving mood and sleep. Some have suggested exercise might even increase the volume of areas of the brain associated with memory[6].

2

2

Something else that may be able to change our memory abilities is our emotional state. One study found that when watching particularly suspenseful parts of films, participants payed less attention to peripheral information – even when that information was presented in a pattern that the brain normally focuses on[7].

Learn more about Consequences of Suspense.

2

2

Whilst some suggest particular proteins responsible, exactly what it is in the blood of the young animal that causes these improvements is yet to be discovered! There is also evidence that effects work both ways – older blood has a detrimental effect on younger mice. These findings raise interesting potential for the future of rejuvenating technologies – if they translate to humans.

2

2Interestingly, some people's brains seem not to be affected by age in the way most others are. These so-called super-agers show similar patterns of brain activity to younger participants in memory tasks, and they don’t show the same shrinkage in memory-related brain areas seen in most older people. Unfortunately, we don’t yet know why some people seem safe from cognitive decline, but it is likely to be at least partly down to their genes.

2

2Immune memory

Is it just our brains that remember, or can our bodies remember too? Scientists often talk about immune memory – the length of time the immune system remembers a disease or vaccine. Live attenuated vaccines usually produce stronger immune responses than deactivated ones, and so the body remembers the disease better, and longer. However, vaccines can and do wear off. Recent discoveries suggest that the body has a long term and a short term memory in the immune system, so some immune responses can be strong, but short-lived, allowing the disease to be caught again and again. One example of this is cholera: catching cholera provides a long-lived immune response, the body remembers it and develops immunity, but scientists have not been able to replicate this with cholera vaccines, which provide only short-term immunity that wears off if you don’t keep having boosters. Researchers are now using the new information about possible long and short term immune memory to develop vaccines that target the long term immune memory.

3

3

Smell is probably the least well understood of our 5 main senses, and is strongly associated with memory – but we don't know how or why.

.jpg)

Memory is a fascinating topic because it is so personal – our memories are what make us individuals. However a huge amount is still to be discovered about how our brains have this seemingly limitless capacity for information. Until this is better understood, it will be difficult to tackle the memory problems which become more of a concern with each passing year, as our population ages.

This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Ginny Smith, Cait Percy, Johanna Blee, Rowena Fletcher-Wood, Joshua Fleming, and Alice Carstairs.

This article was first published on 2016-04-08 and was last updated on 2021-07-24.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Miller, G., (2012). How are memories retrieved? Science 338(6103):30-31. doi: 10.1126/science.338.6103.30-b.

[2] Anderson, M. and Hanslmayr, S., (2014). Neural mechanisms of motivated forgetting. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 6/18:279-292. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.002.

[3] Latorre, Eva, et al. Mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide attenuates endothelial senescence by selective induction of splicing factors HNRNPD and SRSF2. Aging (Albany NY) 10.7 (2018): 1666. doi: 10.18632/aging.101500.

[4] Rasch, B. and Born, J., (2013). About sleep's role in memory. Physiological Reviews. 93/ 2:681-766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012.

[5] Iqbal, K., et al, (2005). Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Molecular Basis of Disease 2–3/1739:198-210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.008.

[6] Whiteman, A,S., et al., (2016) Entorhinal volume, aerobic fitness, and recognition memory in healthy young adults: A voxel-based morphometry study. NeuroImage 126:229-238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.049.

[7] Bezdek, M., et al., (2015) Neural evidence that suspense narrows attentional focus. Neuroscience 303:338-345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.

[8] Katsimpardi, L., et al., (2014). Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science 344(6184):630-634. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141.

[9] Villeda, S,A., et al., (2014). Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nature Medicine 20(6):659-663. doi: 10.1038/nm.3569.

Blog posts about memory

Recent memory News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles