Genes

Article curated by Ginny Smith

Our DNA provides instructions to make every part of our body... but we still don't know exactly how it works.

Things we don't understand about our genome

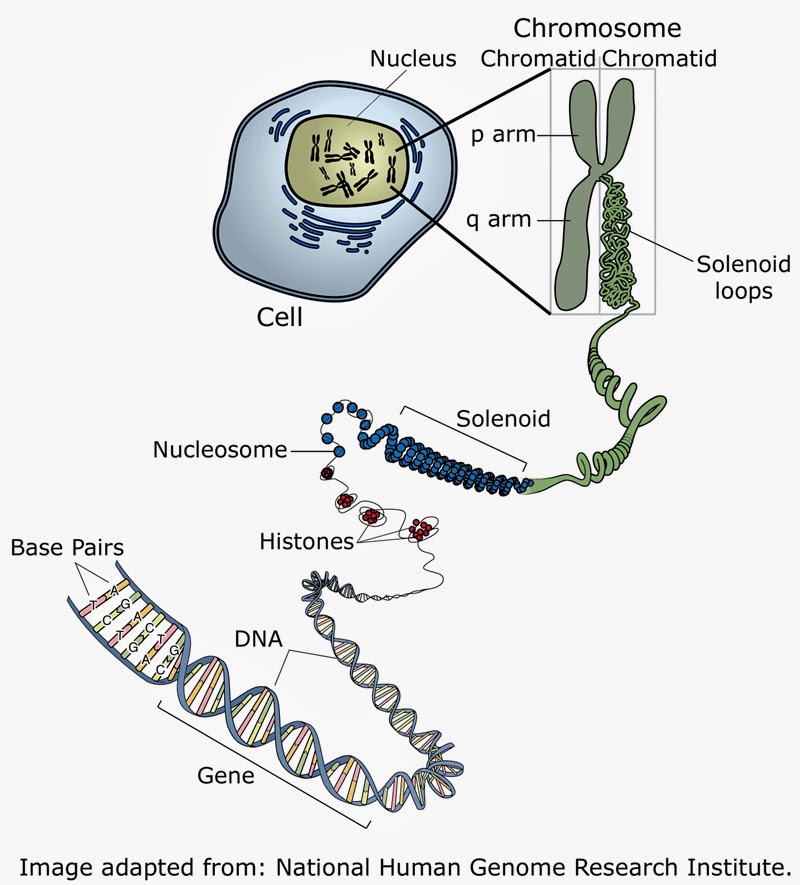

Our genes are what make us who we are – they provide the instructions that allow our bodies to build all the proteins we need. The exact number of human genes is as-yet unknown, but current estimates put it at 23,229. This is surprising when you consider that a water flea contains about 30,000!

So why do we have so few genes? We don't even have one for each of the basic proteins we require. In fact, protein-coding sequences account for only a very small fraction of the genome (approximately 1.5%). This isn't as big a problem as it sounds though – genes don't code 1 for each protein. One gene can be rearranged to provide information about several proteins, for example. The complexity of the process, however, means it is still not fully understood.

The fact that we can hold enough data in so few genes is, in itself, incredible. It is thought that interactions between DNA, RNA, proteins and chemicals all affect when and where a gene will be turned on or expressed. This allows huge complexity to emerge from a relatively small number of genes. How exactly this works, however, is poorly understood. Recent advancements have suggested that something known as 'alternative splicing' may be involved. This is a system by which different parts of the gene are activated at different times, and it is the combination, rather than the specific region, that code for proteins. But even this doesn't give us the full picture of how you can build something as complicated as a human being from such limited instructions.

Learn more about Gene Regulation.

3

3Microbes may have the power to switch on genes, or be selected by genes. The microbes that get on well in our body may even be genetically selected. This can be studied through the differences between caesarian and vaginally delivered babies, although the proposition that birth carry its influence into later life is hotly debated.

Learn more about /microbiome.

3

3Identical twins can be used for all kinds of genetic research, including identifying which diseases or traits show a probability of being expressed, or have an environmental trigger – such as handedness or type I diabetes

2

2

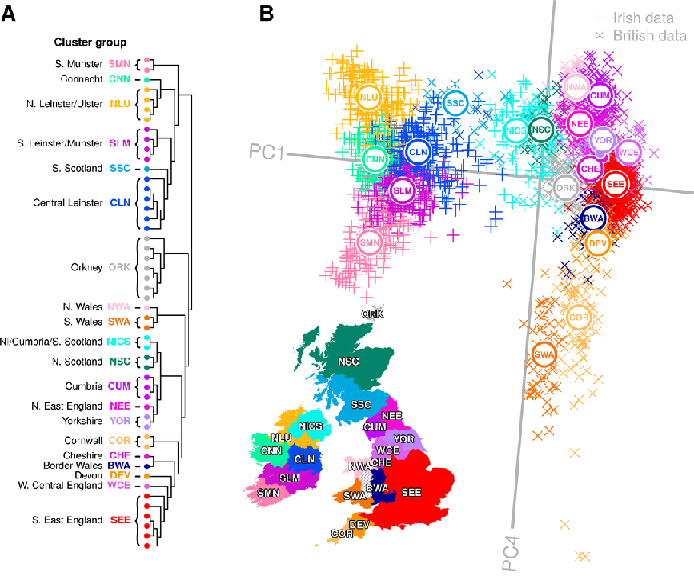

History and genome

What scientists have been able to find by studying the genome, however, is links to geographical ancestry. That is, in the UK, about 0.1% of the unique part of our genome can identify one of 15 million unique geographical areas. Comparing this to the DNA of people across Europe is helping elucidate the migratory history of Britons. The length of a common piece of DNA can be used to work out how far back in the past those two people had a common ancestor. People who have children with others locally over many generations have more recent shared ancestors, and so can “code” for that area. There are still differences between regions that scientists are working to decode, and some are harder than others. For instance, people from Orkney, Wales, and the south west tip of England can be more strongly differentiated from other regions, whereas people from the east of England are indistinguishable over a much larger area. Ancestry sharing can also tell us about ateahistorical mixing of two previously-isolated populations, and when this might have occurred. For example, scientists have found Norwegian DNA in people from the Orkney Islands dated to 1100 CE (with 95% confidence 830CE to 1418CE).

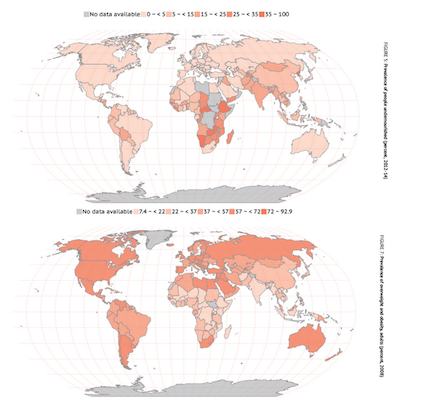

Invasion dynamics – the spread of genetic diversity in animal populations – is another interesting geographical and genetics area of study, which leads to learning about crossbreeding, migration and habitat loss. However, it remains tricky to study because of the challenges of tracking animal populations.

Scientists are still exploring the DNA profile in search for understanding of where white skin came from and why it stuck around in Europe. Genetic history now suggests it developed 40,000 years after Europe was colonised, and that the early Europeans fell into two groups, one with fairly dark and one with very dark skin. Scientists have theorised that the evolution of white skin may be linked to the development of agriculture and lower vitamin D in the diet – because lighter skin absorbs more sunlight and helps us to make more vitamin D.

Research at the University of Sheffield has shown that humans still have the network of 400 genes from our common ancestors with sharks that could allow us to regrow teeth after we have lost them. However, at the moment researchers are still looking into how to switch these genes on and how to regulate growth or switch them off again once they are switched on. This is important to avoid a problem known as supernumerary teeth (too many teeth), which has been reported in humans.

Another thing scientists are interested in is whether we can inherit memories. Research suggests that we might be born with memories from our ancestors imprinted on our DNA, especially traumatic events. This could explain basic survival instincts, phobias and savants. Rodents have been shown to breed-learn into the next generation, so that mice taught a maze have offspring that are more maze savvy than other mice. Tests in nematode worms suggest genetic memories could be passed on as many as 14 generations.

2

2Are high cholesterol levels inherited or caused by nutrition? For many years, it was assumed it was nutrition, but some scientists now argue the other way, following discoveries that high fat diets like the Mediterranean diet do not see higher levels of heart disease, and that the health and food availability of not your parents but your grandparents has been linked to your chances of heart disease, weight gain, and other dietary-related conditions[1].

Researchers looked at the records of nearly 3500 births and discovered a connection between height and pregnancy length. The team don't know the exact cause yet, but believe it must be in a set of unknown genes. It was added that a "woman's lifetime of nutrition and her environment" are likely factors too.

2

2Genetic abnormalities

Sometimes a foetus inherits a faulty gene, or copying errors occur when cells are dividing early on. This can lead to birth defects, health problems, or a miscarriage (accounting for about 50% of miscarriages). Genetic or chromosomal abnormalities are more common for older parents[2]. We don't know why.

2

2

People tend to be attracted to people who look fairly similar to them, or their parents. This seems counter-intuitive as mating with someone genetically related to you lowers the fitness of your offspring! Theories include the suggestion that gene compatibility plays a role, but we don't know. Cultural taboos around incest may have evolved to counteract this drive.

Learn more about Telomeres.

2

2We know that people react differently to different drugs and lifestyles, and that your genetics are important in these reactions, but isolating the genes responsible is a mammoth task. Some genes that increase your risk of developing certain diseases (e.g. breast cancer) have been discovered, and are beginning to be used to allow people to take preventative measures. In many cases, however, it is a combination of genetics and environmental influences that leads to a particular disease developing. One day, genetic testing may lead to medicine personalised for each individual, and help us to live longer and healthier lives. For the moment, however, for most diseases, that day is a long way off.

2

2

Learn more about /sleep.

2

2

2

2

Congenital anosmia

It is very rare, but due to genetic mutations, some people are born unable to smell. This is known as congenital anosmia, and is estimated to affect 6,000 people in the UK. We don't know exactly which genes are involved. However, one candidate is Ift88. In mice, knocking out this gene eliminated olefactory cilia, causing anosmia. The researchers were then able to restore the mice’s sense of smell by using gene therapy – injecting a virus carrying a working version of the gene into the nose. These mice were then able to use smell to find food.

2

2Specific language impairment

Around 3% of children have particular difficulty learning to talk or understand language for no obvious reason. Twin studies from Oxford University strongly suggest a genetic component, but the specific genes and how they act have not yet been identified. For example, children who have an extra X or Y chromosome are at particular risk of speech and language difficulties, despite having broadly normal intelligence, and their language abilities vary hugely. Researchers are also interested in whether the genes that cause a risk for specific language impairment are implicated in other conditions such as autistic spectrum disorder and developmental dyslexia, since many children have both.

2

2Schizophrenia

Nobody knows what causes schizophrenia, but most scientists attribute the disease to an environmentally-prompted expression of genetics, a theory backed up by the statistics relating to twins with and without the disease. However, no single gene has been identified, and scientists think a (so far unidentified) combination of genes is more likely. Environmental triggers appear to be varied and are difficult to measure and regulate.

2

2

Autism

We have no general definition for what defines autism at the level of the cell or brain and so study everything associated with the condition without much understanding of whether the relationship is causal or correlational. Over 3,000 genes have been associated with autism, with approximately 100-200 genes considered "strongly associated". However, just because a gene mutation occurs more frequently in a particular sub-population doesn't necessarily mean that the gene has caused the condition of interest. It's also highly unlikely that all or most converge onto a single behavioural trait. Some of the same genes which were probably false positives in cancer studies are also high up on the autism list. These genes in particular are known for their high mutation rates.Learn more about Genetic causes of autism.

Carpel tunnel

It is generally agreed that there’s a genetic basis to carpal tunnel syndrome, but this basis is not well understood. Researchers into nerve injury are looking to explore the pathophysiological origins of the disease and its link to inheritance.

Travel sickness

Scientists are convinced that travel sickness is caused by an imbalance in the inner ear. This, of course, means everyone has the potential to be travel sick – but we know some people are, some people aren’t, and some get it worse than others. Why? Scientists suggest this may be due to unidentified brain differences that make us better or worse at processing motion, and these could be genetic: if your parents get travel sick, you’re five times more likely to get travel sick too.

Sports injuries

Even sports injuries may be inherited. Research found that inherited knee joints, bone shape and gait may lead to vulnerability to anterior cruciate ligament injuries, and have so far identified two of the genes responsible.

Jumping Frenchmen of Maine

Jumping Frenchmen of Maine disorder is an exaggerated startle response condition with onset after puberty identified in French Canadian lumberjacks in Maine in 1878. The origin of the disease in unknown, but believed to be a convulsive tic neuropsychiatric disorder similar to Tourette’s. Geographical and familial clustering suggests a genetic component. Others think it may be somatic – due to a gene mutation that occurs after fertilisation and is not inherited or passed on – this might make it environmental. Another solution is a culture-specific behavioural syndrome due to operant (punishment-reward) conditioning.

Alzheimer's

Alzheimer's is another disease that may be genetic – many cases can be attributed to mutations in a protein called APOE, but the mutation only increases the risk of an individual developing Alzheimer’s, and does not guarantee the onset of the disease.

Changes in the epigenome of Alzheimer’s patients (methylation that increases with age) suggests that a complex interaction between genes and the environment may be at play[3].

Porphyria

Scientists have discovered a genetic mutation in the UROD gene in 20% of those with porphyria, the “vampire disease”, which inhibits an enzyme needed in haem production. The other 80% are considered to have developed the disease because of environmental factors like alcohol abuse, although this kind of porphyria also seems to run in families, an observation that cannot currently be explained.

3

3

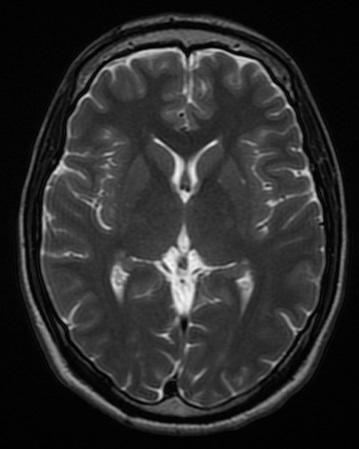

Psychopathy

After neuroscientist Jim Fallon identified patterns in his own brain similar to those of the psychopaths he was studying, he coined the phrase "pro-social psychopath". He claims that you can have the brain characteristics but not behaviour of a psychopath, and that this demonstrates that the genetic condition is activated by environment. There is some controversy around this self-diagnosis and the methods used to obtain such findings.

Genetic modification

“Sleep mutant” animals have been identified and created, although how genes link to sleep disruption is still a mystery, since studying sleep in animals .is notoriously difficult to study because the study techniques (such as use of probes) interfere with sleeping. Researchers are now using cameras to monitor sleep disruption in mice.

Learn more about /sleep.

2

2Scientists can’t currently be sure that gene editing is “unconditionally beneficial”. In the edit that produced the first genetically-modified babies, scientist H. Jiankui disabled their CCR5 genes, making them HIV resistant. However, later work showed that people with two edited copies of this gene are 21% more likely to die before age 76[4]. The reason is unknown.

2

2Researchers at King's College London have successfully delivered genetic material using a virus to repair spinal cords. After the therapy, previously paralysed rats were able to pick up and eat sugar cubes with their front paws.

Horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer describes the evolutionary process by which genes from one organism are assimilated by another, attributing new features and survival mechanisms. It’s very common in microbes, and one of the reasons that antibiotic resistance develops so rapidly. However, it is rare in complex organisms such as plants and animals. Scientists are currently interested in investigating the range of organisms which perform horizontal gene transfer and whether the process is one- or two-way. The mechanism by which the genetic material is transferred remains a mystery.

Evidence of horizontal gene transfer has been found between parasitic plants and their hosts. Plants such as dodder “steal” genetic material and incorporate it into their own genome in order to maximise their nutrient sequestration from hosts and maybe even silence host defence systems. The process appears to be one-way, with the parasitic plants not sharing their own genetic material in the handover – but this is still being tested, and how the genetic material is actually transferred remains a mystery[5].

Biological sex

Biological sex depends not only on the X and Y chromosome, but also on a host of other genes and their expressions. For example, the genes that make you male or female, such as SOX9, the gene that drives the body to develop testes, are regulated by other genes known as enhancers. This means you can develop testes if you have an extra copy of the enhancers, even if you have two X chromosomes, or develop ovaries if you are missing them, even if you are XY. The enhancers were found amongst the set of DNA formally known as “junk DNA”.

Is it possible to change your sex? Due to the newly emerging data about a complex network of sex genes, scientists think this could be possible. Genes such as DMRT1 and FOXL2, which maintain sexual characteristics during adulthood. If these genes stop working, your gonads could change and start looking like those of the opposite sex, suggesting humans could actually sex change and that, without these genes constantly active, sexual identity could be fluid.

Fingerprints

2

2Some people don't have fingerprints. This is known as adermatoglyphia, and scientists think there may be a gene mutation (in SMARCAD1) responsible. They're still looking into it, however, as the gene might instead be involved in sweat gland development.

Origin of life

Symbiotic theory postulates that two or more cells from different species came together to form the first multicellular life because they derived mutual benefits from a physical association, such as one consuming the waste product of another. As the cells evolved, the theory suggests it became impossible to dissociate and exist independently, and eventually fused their genomes to make a species and single germ line, whilst maintaining different cellular phenotypes via differential gene expression. Evidence for this theory includes lichen, which are made from different genetic algae and bacterial species that live and work together symbiotically. A problem with the theory is the process by which how different genetic codes can merge – no other biological indication of this happening has been found to enlighten us.

A further question is how cells evolved "selfishness" and yet started cooperating to create multicellular species.

We don’t know how life began, but a proof-of-concept prototype quantum algorithm has produced data that mimics real life biological data pretty accurately. This result, obtained by encoding behaviours linked to self-replication, genetic mutation, and individual interactions, shows that quantum mechanics may be more intimately linked with the origins and nature of life than previously believed. Scientists are still trying to work out how.

2

2This article was written by the Things We Don’t Know editorial team, with contributions from Rhi, Emily L. Williams, Ginny Smith, Cait Percy, Johanna Blee, Rowena Fletcher-Wood, Joshua Fleming, and Alice Carstairs.

This article was first published on 2015-08-27 and was last updated on 2020-07-20.

References

why don’t all references have links?

[1] Bygren, Lars Olov, et al. Change in paternal grandmothers early food supply influenced cardiovascular mortality of the female grandchildren. BMC genetics 15.1 (2014): 12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-15-12.

[2] van den Berg, Merel MJ, et al. Genetics of early miscarriage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 1822.12 (2012): 1951-1959.

[3] De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, Burgess J, Schalkwyk LC, Yu L, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014 Sep;17(9):1156–63.

[4] Wei, X. & Nielsen, R. Nature Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0459-6 (2019).

[5] Yang et al. 2019. Convergent horizontal gene transfer and cross-talk of mobile nucleic acids in parasitic plants. Nature Plants. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-019-0458-0.

Blog posts about genes

Recent genes News

Get customised news updates on your homepage by subscribing to articles